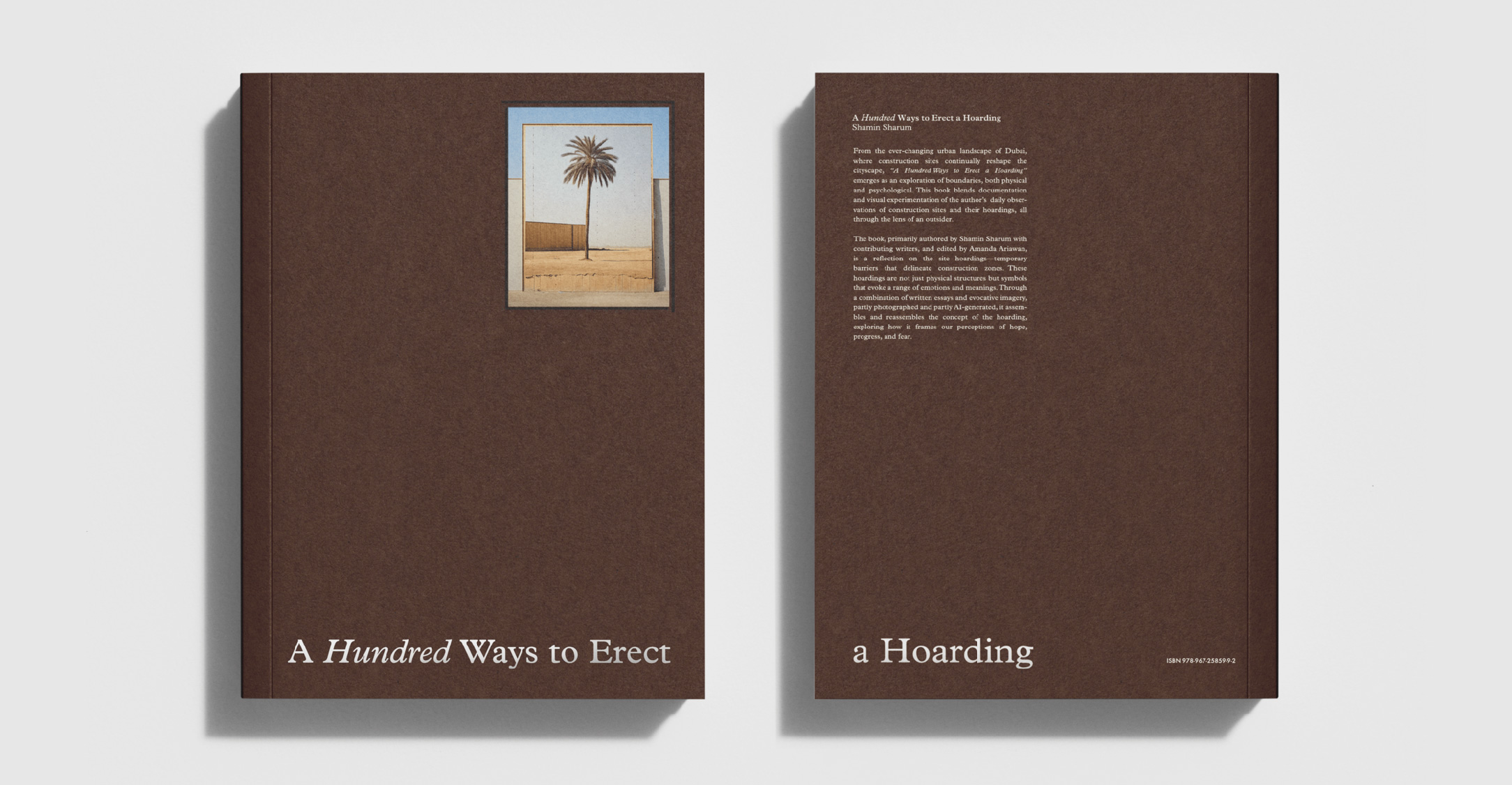

A Hundred Ways To Erect a Hoarding: Speculating on Space and Machine

Designer: Shamin Sharum

Scope: Publication

Publisher: Suburbia Projects

A Hundred Ways to Erect a Hoarding is Shamin Sharum’s retrospect on the evolving urban landscape, specifically set in the city of Dubai, United Arab Emirates. The book examines how rapid construction continuously reconfigures the city’s landscape through an ephemeral lens that presumes its development to be an atomized phenomena. As a Malaysian residing in Dubai, Shamin coalesced his interests in art and architecture through this singular publication. Collaborating with Suburbia Projects—an independent architecture-focused publisher based in Petaling Jaya, Malaysia—he released the book in 2024. This publication features not only Shamin’s visual documentation and artistic experimentation but also a series of essays on urban development and artificial intelligence, contributed by Huat Lim, Clara Peh, Amanda Ariawan, Jowin Foo, Danishwara Nathaniel, and Shamin himself (credited as the project’s initiator).

The project emerged from Shamin’s daily observations of construction sites, both during his time in Kuala Lumpur and his relocation to Dubai. As an outsider, he was compelled to shift his gaze in examining construction: away from his positionality as a distant stranger but embracing closer involvement as a near-participant. Despite the foreignness of Dubai’s development context, he drew correlations to the various construction sites he had encountered before in Malaysia. He turned his attention to everyday objects rather than the urban-centric conventions of monumental buildings, as they are often overlooked due to their temporary nature. Through this narrative, the book (re)constructs the concept of borders (both physical and metaphorical) by using construction hoardings as a conceptual framework to reflect on perception; pondering on what we project upon these structures and in return, what they mirror onto our line of reflection.

The first boundary that Shamin faced was cultural, rooted in the different interpretations of what constitutes the ‘urban’ between Kuala Lumpur and Dubai. As he shared in a conversation with Jowin Foo, Shamin has a habit of reading cities through their minor elements—such as the cobbled streets of Amsterdam or the red telephone booths in central London. Identifying these features-intimate to each city- helps him find a sense of normalcy within unfamiliar urban environments. In Dubai, it was the construction sites that became recognizable to pivot the new landscape that Shamin entered. He determined these sites as integral to the architecture of postmodern reality, shaped by the global standardisation of materials. Upon recognising this sameness, he took notice of subtle differences that shape local construction cultures—such as the types of hoarding materials used or the configurations of barricades. Rather than seeing Dubai through its glitz and glamour, he chose to focus on the textures he encounters everyday.

The second boundary he explored concerned conceptualisation of reality and imagination. Through the function of the hoardings, he examined the tension between the visible and invisible–what lies beyond its periphery and what remains exposed to the public eye. These two realms exist in relation; requiring one another to complete its definition. His interest in the hoardings extends beyond its typical use as physical barriers, but in its relativism, particularly in shaping our perception of what constitutes the ‘hidden space’. In this context, boundaries are mental constructs, with imagination playing a pivotal role in shaping spatial perception. Together, they give meaning to space. While buildings often reflect cultural identity through style and ornamentation, construction sites, in contrast, are presented as culturally neutral voids—waiting to be filled with interpretation.

While the first boundary shaped how Shamin perceived his environment, the second influenced his artistic choices to explore what is referred to as a representational dilemma. Shamin merged documentation with speculation by incorporating AI into his creative process. He used fieldwork and photography to document the fast-changing construction sites, while also simulating imagined spaces using what is referred to as “promptography.” Coined by Peruvian photographer Christian Vinces, promptography involves generating images from text prompts using machine learning systems. As Clara Peh writes in the book, these systems—such as DALL-E and Midjourney—are often referred as black boxes due to their opaque mechanisms. Unlike photography, which captures light to form an image, promptography is driven by language and algorithmic interpretation and produces visualizations that might be read as digital hallucinations. Shamin deliberately blurred the distinction between AI-generated and real photographs, encouraging the viewer to question the authenticity of their materialities. At this point, Shamin embraces the representational dilemma and he continues to thread the boundaries between reality and imagination.

Crucially, the book does not rely on a singular artistic viewpoint. The use of AI image-generation technologies has also been subject to cultural critique. Amanda Ariawan examines the inherent biases in these technologies and how they shape our perception of the world. AI models are trained on vast datasets that often compress its diversity into digestible-and-repetitive visual tropes. Amanda’s research reveals how these systems amplify bias, especially when they are being trained on skewed datasets. This argument is further supported by Danishwara Nathaniel’s exploration of how AI-mediated relationships between image and text reflect colonial-era power structures. The images produced by AI offer insights not just into the technology itself but also into the data it consumes and the asymmetrical power dynamics embedded within its systems.

A Hundred Ways to Erect a Hoarding does more than speculate on construction sites and urban development—it urges readers to cultivate an attentiveness to the everyday sublime: those mundane moments that carry quiet tension, beauty, and complexity. By paying close attention to often-overlooked visual landscapes, the book challenges us to question what we accept at face value. In a world saturated with images, critical observation becomes an essential skill not only to understand the world more deeply, but to recognize how visuals continuously shape our perception of reality.