Veiled Truths: Memory and Resistance in Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis

A search for meaning anchors the narration of history, binding together those who create it and those who receive it. To historicize is to wield power: the language used to frame the past can define it—not only for the self but for others. This act of definition becomes a means of shaping identity, culture, and collective memory. Simply put, we look to the past to understand ourselves—and this cycle continues across generations. Art, literature, cinema, and other creative mediums often become acts of witnessing. They stand as testimonies to lives both lived and lost, and are transmitted through the subjectivity of the artist. One might argue that the artist assumes a dual role: as a storyteller and as a bearer of truth. In many cases, this truth challenges the absolutism of History presented in official records or any form of national histories. Creative works, then, can become acts of resistance—expressing suppressed narratives or voicing the (collective) silences of a people.

This is particularly evident in the work of Marjane Satrapi, whose autobiographical graphic novel Persepolis has reached global audiences and critical acclaim. Published between 2000 and 2003 in two parts, the first—Childhood—recounts her upbringing in Tehran during the 1979 Islamic Revolution, while the second—Return—documents her migration into Europe and eventual return to Iran. Through this transnational journey, Satrapi gained the distance necessary to reflect upon her memories and identity, ultimately forming a perspective that is both arguably Iranian and diasporic.

The book’s success led to the 2007 film adaptation, where Satrapi had written its screenplay, which retained the visual and thematic language of the graphic novel. Similarly, the film was celebrated for its political sensitivity and emotional depth. Its popularity, particularly among Western and international audiences alike, suggests a widespread hunger for intimate, humanising portrayals of Iranian life—stories not mediated by headlines or propaganda, but by lived experience.

Part of Persepolis’ impact stems from its capacity to challenge dominant narratives about Iran. At the time of its release, stories about the country were overwhelmingly shaped by Western media, which were often discussed in connection to what Satrapi wrote as “fundamentalism, fanaticism and terrorism”. At the same time, there are absolutist narratives that were circulated by the Iranian republic/state that painted the Revolution to be entirely benevolent– in effect, erasing the dissent and complexity that constitutes its movement. She refused both of these simplifications and articulated in her own words:

“I believe that an entire nation should not be judged by the wrongdoings of a few extremists. I also don’t want those Iranians who have lost their lives in prison defending freedom, who died in the war against Iraq, who suffered under various repressive regimes, or who were forced to leave their families and flee their homeland to be forgotten.”

This framing highlights Satrapi’s dual mission: to honour the histories that are intimate to Iranins and to refuse the flattening of Iranian identity. However, it is essential to receive Persepolis not as a universal representation of Iran, but as one deeply personal and partial account—an artistic rendering shaped by memory and displacement.

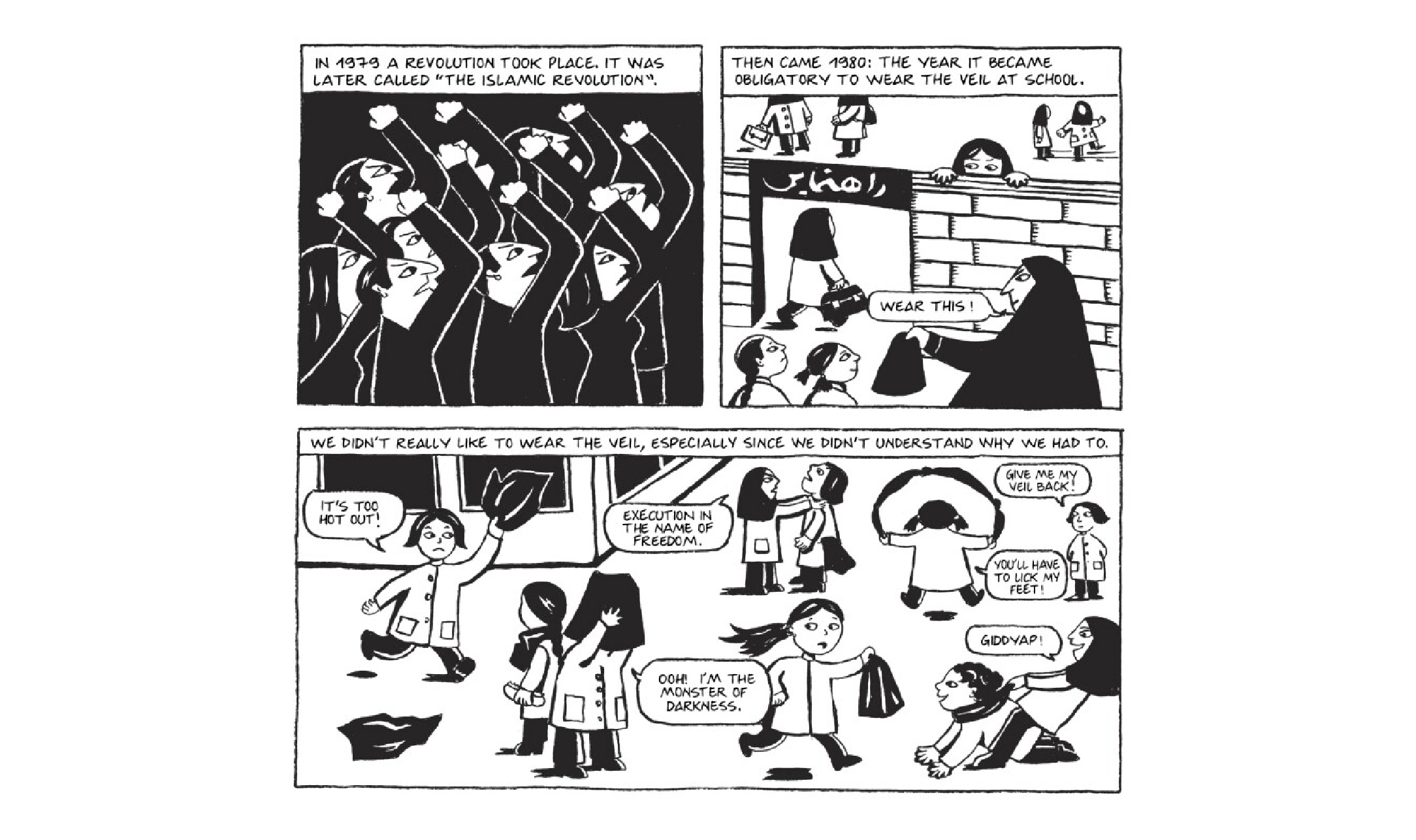

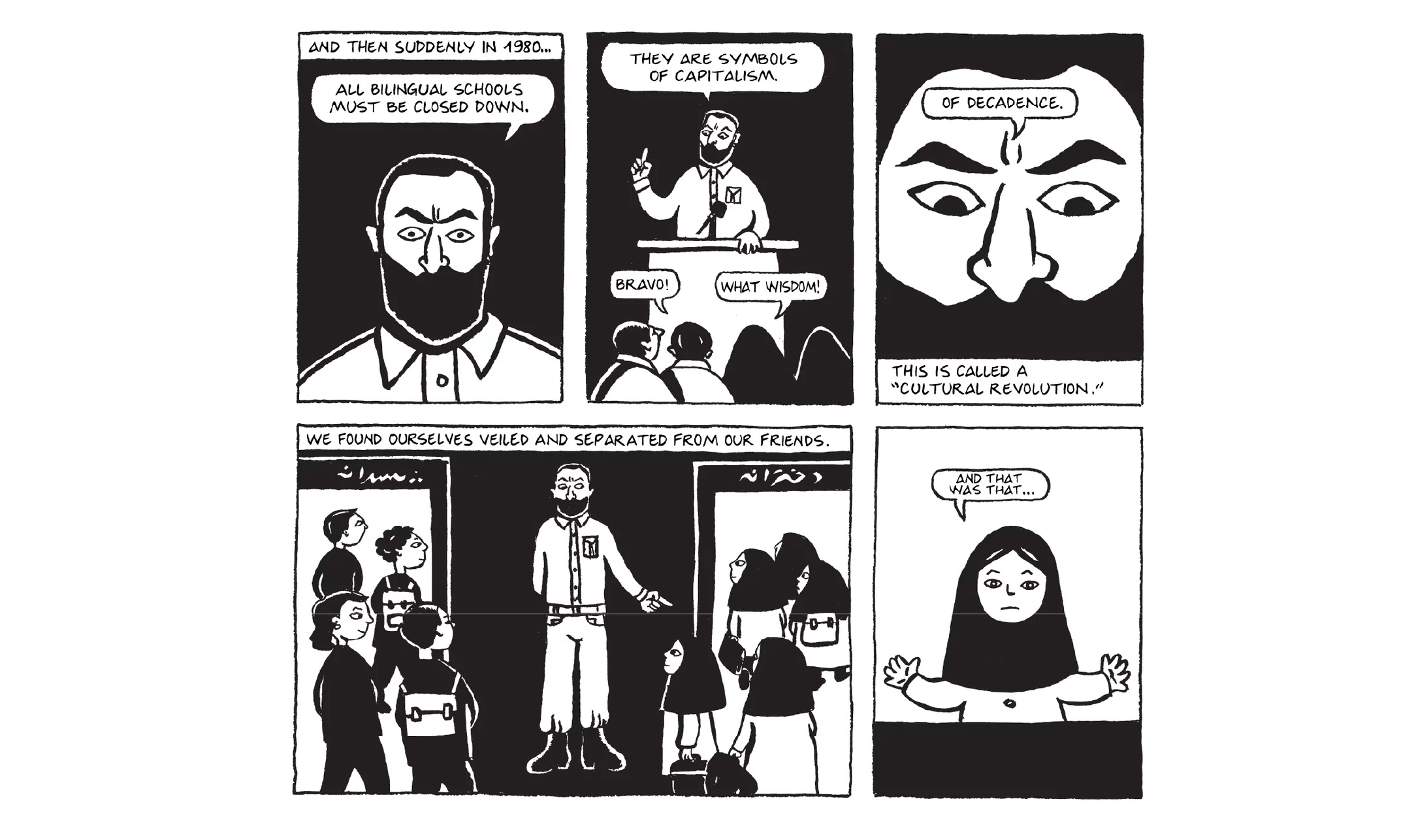

Visually, Satrapi’s graphic style is minimal yet evocative. She adopts a black-and-white palette that carries both aesthetic and symbolic weight. On one hand, it recalls the comic-strip format popular in the late 20th century; on the other, it visually echoes the stark dualities imposed by ideological systems—light and darkness, right and wrong, faith and freedom. Yet Satrapi resists moral binaries in her storytelling and opts to be expansive in her language and by extension, her illustrations. Instead, her world is populated with contradictions, compromises, and pain.

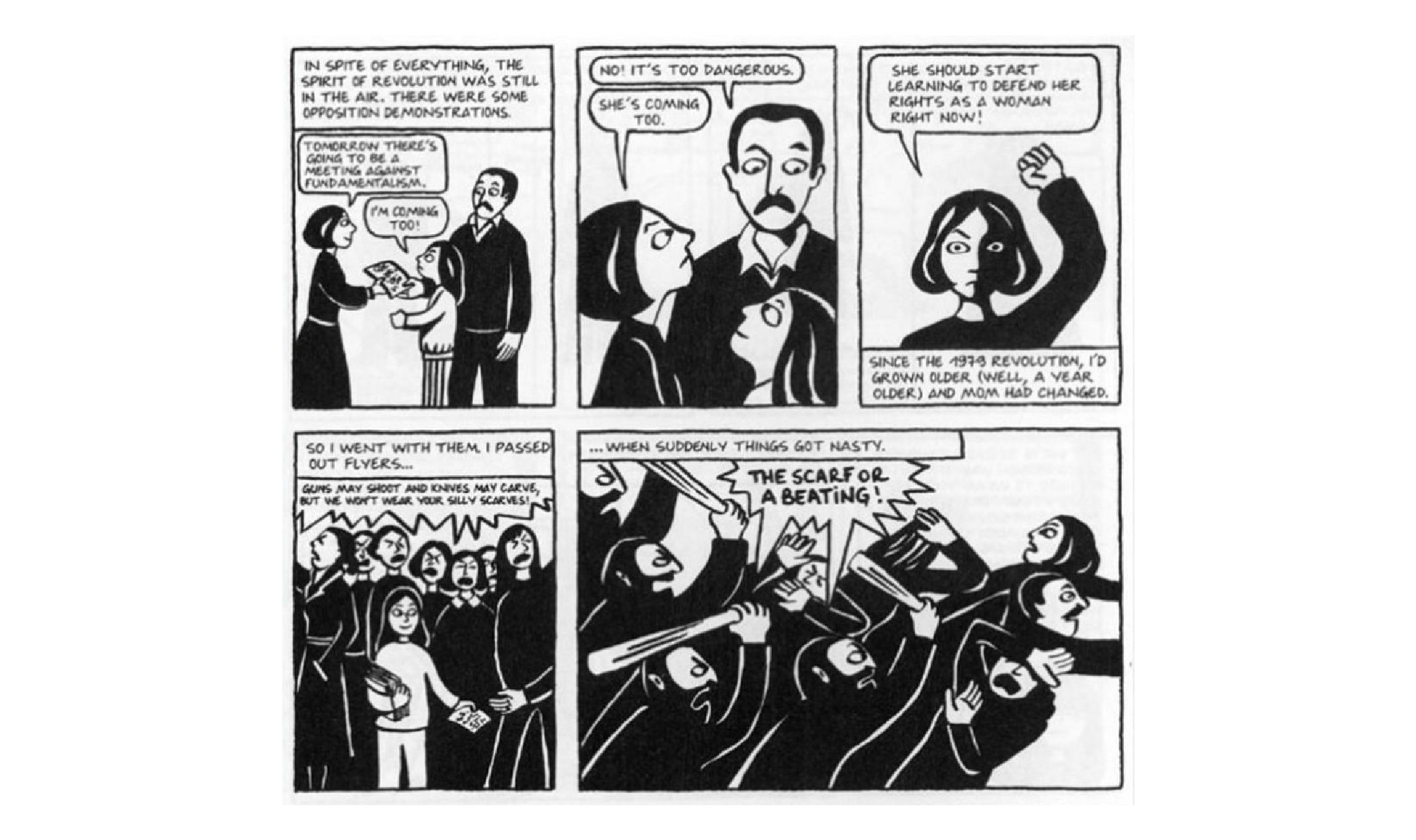

The visual style also emphasises accessibility upon reception (in sight). By stripping down details, she invites a universal reader to engage with her story, while simultaneously tending to the emotional weight of each scene: in her graphic novels, every chapter is introduced under a symbolic theme (i.e. Socks, Exams, etc.) and its illustrations are drawn in response to said topic. What emerges is a simple-and-strong-enough narrative where each individual chapter can hold to its own, whilst existing as an important part that collectively forms the world-building of Persepolis. Panels move between intimate domestic moments, and sweeping public events with seamless fluidity, reminding the reader that history is always lived in the body, the home, and the everyday and politics traverses the public and private spaces.

One of the most compelling motifs throughout Persepolis is the veil (hijab), which functions both as a personal symbol and a political object. From the very first chapter, Satrapi expresses discomfort with the veil, which became mandatory for women and girls following the 1979 Islamic Revolution. For her and her secular family, the veil represented an abrupt rupture with their values and way of life. In one memorable panel, Satrapi ponders on her difficult reaction to the veil. This echoed into the way she depicted a group of girls during her childhood: Iranian girls—herself included—become nearly indistinguishable, visually echoing the loss of individual identity under imposed religious codes.

At this segment of Satrapi’s life, the veil is shorthand for the broader system of control enacted on women’s bodies and movements, enforced by the morality police. These agents of the state-patrolled public spaces, reprimanding those who dressed "inappropriately." Satrapi recounts her own encounter with them, when she was stopped for wearing Western-style clothes: a denim jacket and sneakers smuggled into Iran by her parents. The incident left her shaken, illustrating the psychological and physical toll of living under surveillance.

But Satrapi’s treatment of the veil evolves as she moves across countries. In the Return chapters where she had moved to Vienna, Marjane signified hair as a newfound symbol of freedom. Her hairstyles change alongside her identity: a punk cut in adolescence, an awkward shoulder-length look during puberty, and so on. Hair—visible, flexible, personal—stands in contrast to the concealment of the veil. These moments of self-styling mark phases of experimentation, cultural clash, and self-discovery in distance.

When Satrapi moved back to Iran as a young adult, the veil once again became unavoidable. Initially, she experiences it as suffocating; reflection of her initial feelings of return. However, she begins to observe the subtle variations in how women wear it: some let strands of hair show, others choose longer, more conservative styles. In one sequence, she drew the different veil styles of her classmates, linking them to their presumed political affiliations or values. Even within constraint, there is negotiation, meaning, and identity amongst Iranian women.

This complexity of the veil is part of what made Persepolis groundbreaking, as it provided nuance into what was perceived to be identifiable with Iranian life. Rarely had an Iranian woman spoken so candidly towards an international literary market about their complicated relationship with state-imposed dress codes. However, this visibility also drew critique. Some accused Satrapi of promoting Orientalist tropes—depicting Iran as inherently repressive, Iranian women as universally oppressed, and the West as a place of liberation. Others argued that her story reflected a particular class position: upper-middle class, cosmopolitan, and ‘educated’—far removed from the experiences of rural or working-class Iranians who bore the brunt of its turbulence (i.e. violence).

These critiques are important because they push us to avoid romanticising or universalising Persepolis. What Satrapi offers is not a total history of Iran but a fragment—a vivid, courageous, and important perspective that opens space for further dialogue. It is one testimony among many.

The danger arises when this fragment is mistaken for the whole. In global discourse, particularly in Western contexts, there is a tendency to over-rely on works like Persepolis to explain Iran. This reflects a broader failure of imagination—a failure to perceive the depth, complexity, and modernity of Iranian life. Today, this is still evident in the TikToks where users express shock that Iranians dance, cry, or wear fashionable clothes. The subtext is clear: they didn’t expect Iranians to be human in the way that they themselves are.

Satrapi’s work asks us to do better. It reminds us that behind every political headline or historical event, there are individual lives—messy, rich, and contradictory. To historicise through personal narrative is to return dignity to those lives. It is to insist that their pain, their joy, and their resistance be remembered.

As the world continues to witness the unfolding consequences of American and Israel intervention, and the regional destabilisation, Persepolis remains hauntingly relevant. In any context of conflict, the burden always- and continues to-falls on ordinary people. In such times, bearing witness is amongst our only forms of solidarity. To tell a story is to resist forgetting. And in that resistance, Satrapi’s Persepolis offers not just memory—but the possibility of empathy, understanding, and maybe action.