Nusaé and the Principle of Harmonizing in Conscious Design

For over a decade, Nusaé has established itself as a studio that sees design as a way to live harmoniously with its surrounding (i.e., social, cultural, economic, and spatial) environments. Under the direction of Andi Rahmat, the principle of harmony has become the connecting thread that runs through the studio’s diverse practices, translated through their spatial information systems and cultural projects to design research. Now, Nusaé encapsulates its philosophical journey in the book Harmonisasi and the exhibition In Continuum: Harmonisasi. Both these outputs established the Bandung-based studio’s ‘signature’ design through the ethos of harmony, and as a way of working within today’s ever-shifting design landscape.

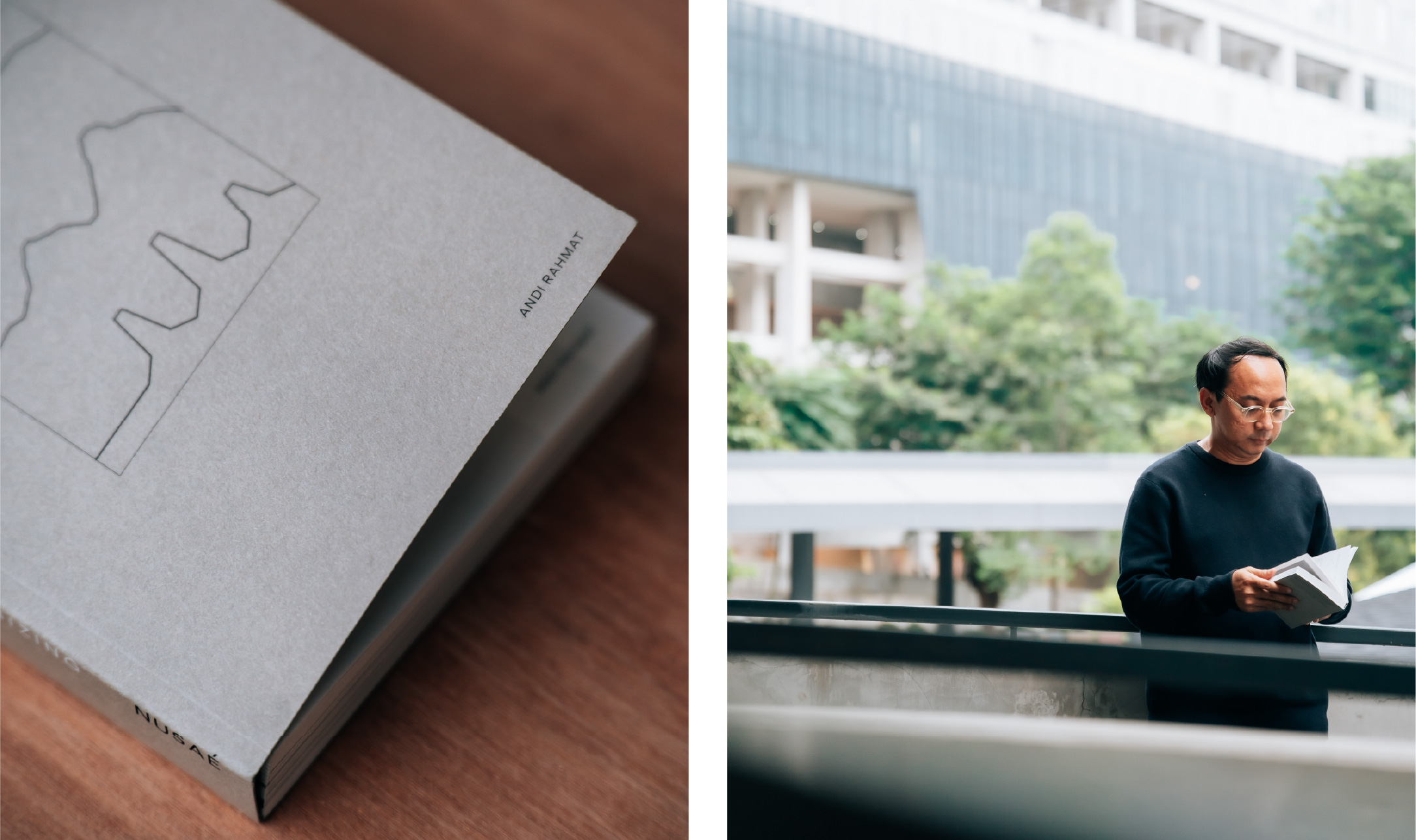

Amid the bustle of Central Jakarta, Andi Rahmat sits with us and explains the ideas behind the book Harmonisasi and the design principles within. For him, “harmony” is not a decorative word displayed on the studio wall; it is a way of thinking and acting that is continuously tested through everyday design practice. “A designer’s role always intersects with many things; not only graphic design, but also culture, economy, society, the environment, even architecture and research,” Andi says. “To be in and to work with harmony is important to shaping our awareness towards our capacity, and relation (to all of these aspects of life).”

That awareness emerged from his long journey as a designer. Andi began his career around 2005, when graphic design in Indonesia was expanding commercially, but it paid minimal attention to depth in design philosophy or principles. Over the course of two decades, he realized that design cannot be viewed merely through its communicative function; it must also be measured by how well it blends with its surroundings.

“For me, harmony is not an end goal, but a method,” he explains. “It’s about realizing that everything we do will inevitably intersect with something else. It’s about how design can coexist with the things it touches.”

The idea of harmony in Nusaé’s context did not appear out of nowhere; it grew from Andi’s personal search for his studio’s identity. “When I founded Nusaé, I felt it was important to have a principle we could hold onto,” he says. “Something that isn’t just about aesthetics, but a way of understanding our position as designers.” That search led him beyond the studio to various regions across Indonesia: Sumba, Kalimantan, Bajo, and other areas beyond Java. There, he found the value of mutual cooperation embedded in local communities. From these observations, Andi arrived at the concept that would become his foundation: “Design connects the unseen.”

“I saw that as designers, we actually connect many things that aren’t always visible,” Andi explains. “Values like mutual help, togetherness, complementing one another, all stem from the awareness of blending without the need to dominate. That’s harmonizing in its most basic form.” For Andi, these values echo the Sundanese philosophy of Sabilulungan: together in harmony. Yet instead of treating it as an intimately local norm, he transformed it into a universal principle — to make harmony as a way of being in today’s design world.

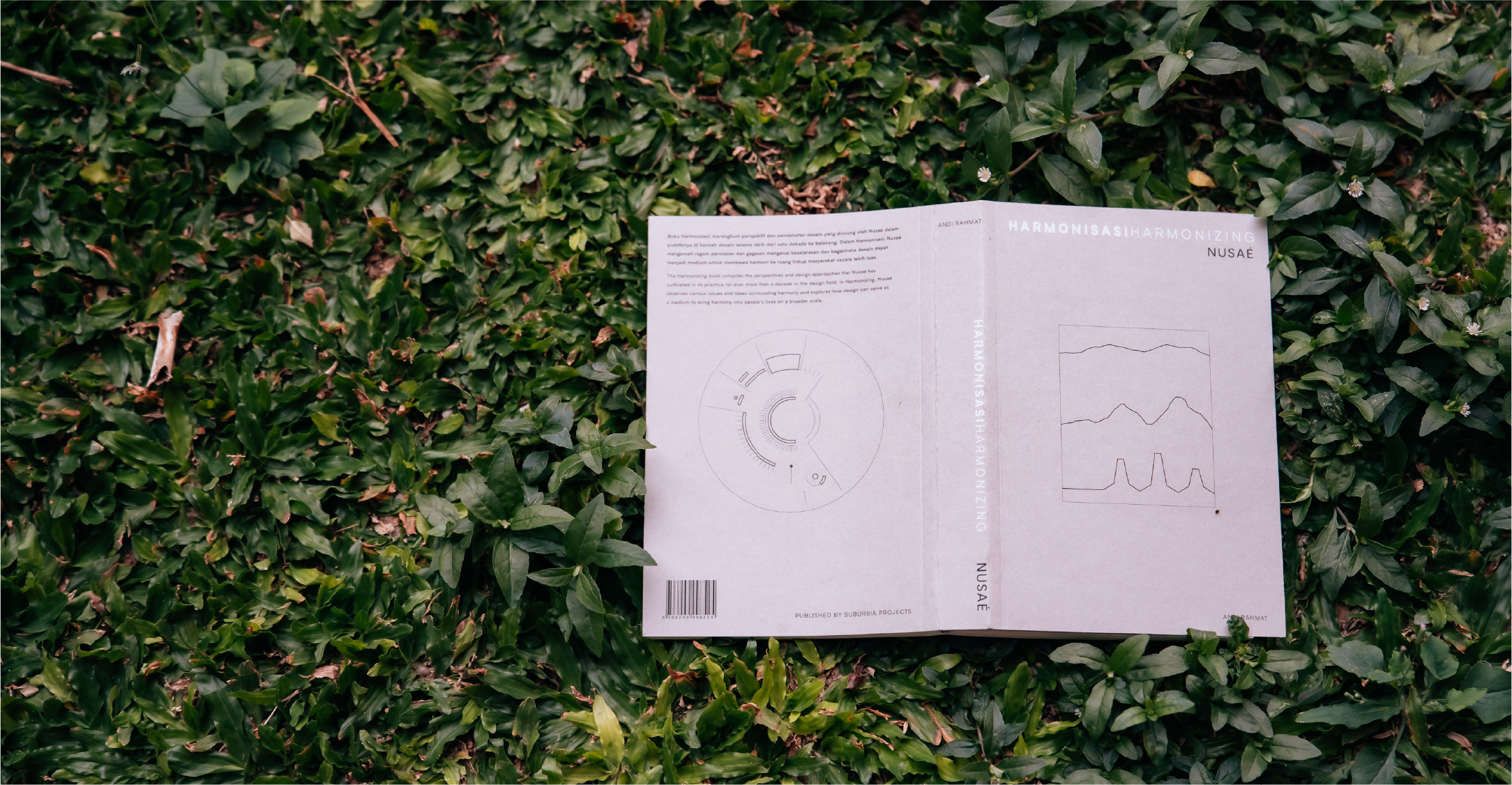

A more detailed articulation of this design principle is presented in the book Harmonisasi, published by Suburbia Project, a Kuala Lumpur-based publisher. Rather than merely displaying portfolios, the book maps out Nusaé’s reflections and conscious design experiences gathered over the past ten years. “This book doesn’t talk about technical processes,” Andi says. “We wanted to explain why we believe in this principle of harmony. From there, readers can understand Nusaé’s perspective on harmony itself, because harmony already exists in nature, long before us. We’re simply learning from its source.”

In the book, readers can also find explanations of Nusaé’s design strategies derived from this principle of harmony. Andi describes six key points implemented in their practice, three of which are: berpadu (coexist), kontras (contrast), and kinetik (kinetic). Berpadu refers to how the studio interacts and exchanges ideas across disciplines; kontras highlights the importance of difference as a strategy to find balance, such as in the Bintaro Design District project, where multiple areas were visually unified yet still allowed diversity; kinetik reflects the digital era, where everything is interactive and constantly moving.

To celebrate the launch of the book, Nusaé is presenting the exhibition In Continuum: Harmonisasi at the new Kopi Manyar space in Bintaro, a small gallery designed by Andra Matin, characterized by its raw and domestic atmosphere. Opening on November 1, 2025, the exhibition is, as Andi describes it, “a way to peek into the book before reading it.”

The exhibition is divided into three chapters. The first highlights figures and works that inspired the idea of harmonizing itself. Among them are Le Corbusier with his Le Modulor principle of human proportion as the basis of spatial form; graphic designer Priyanto Sunarto, who sought to make visual communication clearer through grid systems; and architect Andra Matin, whose Belimbing Sari Airport in Banyuwangi demonstrates a strong harmony between space, culture, and local economy. Through this section, Nusaé aims to show that harmony has always been a thread running through design history—constantly changing and evolving, yet remaining a core principle for creating meaningful works.

The second chapter presents Nusaé’s own interpretation of harmonizing, through two key projects: Bintaro Design District and Tubaba. Both illustrate how Nusaé integrates social and spatial contexts into graphic design practice. In Bintaro, harmony emerges from contrast and collaboration; in Tubaba, from dialogue between design, culture, and regional development. The final chapter focuses on the creative process behind the book Harmonisasi, from cover studies and narrative structure to the role of illustration in strengthening the ideas conveyed. Spatial experience is also an essential part of the exhibition narrative. Inside the gallery, once a residential home, Nusaé arranges wooden furniture and books as part of the installation, transforming the space into a reading room that invites interaction.

On a broader scale, both the book Harmonisasi and the exhibition In Continuum: Harmonisasi can be read as a reflection of Nusaé’s design philosophy. At a time when many design practices are driven by commercial, fast-paced demands, Nusaé seeks a different path: affirming the values of awareness, relationship, and continuity. Yet for Andi, harmonizing is never a final concept. “I don’t want to stop at our current version of harmonizing,” he says. “Each era has its own sense of harmony. Maybe next year I’ll find another form of it. My hope is that those who read the book or see the exhibition can discover their own harmony.”

That statement encapsulates Andi’s perspective on design as an open and ever-evolving practice. “Designers play a big role in shaping public awareness,” he adds. “It’s not just about aesthetics, but how the values of life can be translated into forms that can be experienced collectively.”