To Linger, To Listen: Cato's Paintings

Over the decades, there has been a rise of inclusion amongst the Western contemporary art scene, where more room (to create, exhibit) has been made for artists of colour. They have brought a visual language that challenges the whiteness embedded in the artistic institutions and their aesthetic ‘standards’, breathing a new life into our ways of seeing, and being. Black artists are amongst those who have pushed these boundaries, as their art stands as an expression and reclamation of their identity; bringing forth a conceptualisation and materialisation of Blackness.

Toby Grant (aka Cato), a London-based multidisciplinary artist and musician, emerges as one of the contemporary artists whose work intends to “make sense of my scattered interests and Blackness”. Cato plays with a mixture of mediums – painting, photography, collage, airbrushing, and most recently moving images — and translates their forms seamlessly. He treats these materials not as disparate elements, but allows them to enmesh organically—each material breathing into and through the other—forming a unified expression. This fluidity collapses the functional boundaries within classical art practices, and in doing so, Cato forges a foundation (of artistic practices) that he calls his own.

Cato’s paintings are marked by its cinematic quality, as he imprints a lingering into (our) gaze; demanding the viewer to not just ‘see’, but to watch the lives of his characters unfold. In Barbershop, we witness a haircut in a tiled room rendered in a shade of gray and black-and-white. The barber is deep into his craft, as he carefully inspects the strands of hair to decide the blade’s next cut. Meanwhile, the client is absorbed in a newspaper with headlines that read “Revolutionary Posters” and “The Black Panthers”. The portrait captures a moment of intimacy shared amongst black men, as barbershops are portrayed as a place of community and friendship– a recurring motif in black media. Perhaps one might argue that this specific work leans into a shared experience that belongs to the community, offering an expression of Blackness shaped by commonality. Reflecting on the painting, Cato confessed: “I never went to the barbershop when I was younger and it feels like I missed out.” Thus, we stand with Cato and watch the routine unfold in the Barbershop, experiencing the glimmer and grief of a memory he longs for.

The act of peering in – quietly observing – threads through much of Cato’s works. The monochromatic palette first seen in Barbershop carries over throughThe Block, The Pugilists, The Service, and 3 Musicians, creating a world-building effect that threads across these paintings. Each scene pulls us in and we become enmeshed into their worlds: we walk through the streets, we watch a kick-boxing match, we pray and weep, we dance. In its experience, we are able to feel that Cato’s composition goes beyond the visual, as there is a palatable sense of atmosphere within his paintings. It is only felt, as we peer longer into his world, creating an effect that: the longer we linger, the more we are likely to listen. Suddenly, we begin to hear imagined conversations, the buzz of clippers, distant music, the subtle rustle of bodies in motion that introduce multitudes of colour into Cato’s worlds.

Jazz emerges as a key work in which Cato’s engagement with music becomes both subject and structure. Inspired by his Sunday jam sessions with friends, the painting transcends pure memory, offering instead a portrait of lived experience—where personal ritual meets artistic expression. The scene exudes a bohemian energy, reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s portraits of creative circles: loose, vibrant gatherings of artists, musicians, and kindred spirits. Yet where Warhol's lens was often cool and observational, Cato's is participatory: the viewer is drawn into the rhythm of the room. Cubist inflections fracture the background, where gray blocks give way to vivid flashes of yellow, orange, blue, and pink. The musicians are scattered across the space, each absorbed in their role, collectively animating the composition like an ensemble in full improvisation. In a talk, Cato described how the painting came to life: sourcing faces from old photography books, redrawing and recontextualising them through layered sketches, before transferring them to canvas in acrylic and finally softening the surface with airbrushed white paint. The result is a textured harmony—both formally and thematically—as memory, process, and sound collapse into a single visual tempo.

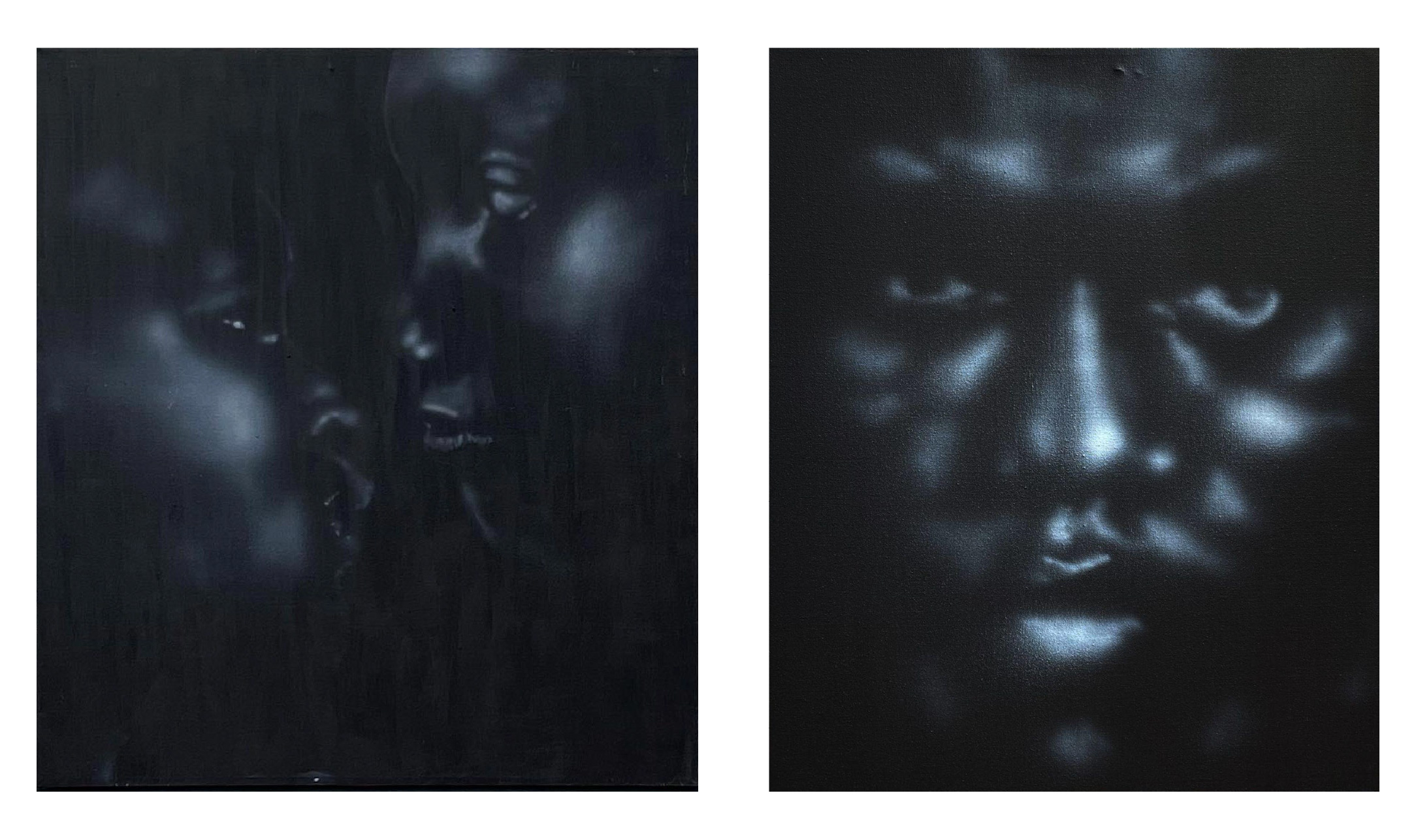

It is apparent that the presence of the black characters anchors the artistic universe that Cato has built. He revealed the origins of these characters: “I was always looking for a way to do a face, to paint a face in an interesting way. And this was the quickest and the funnest way, to create an immediate contrast of light-and-dark.” They do not stand as an aesthetic expression or a claim to Cato’s artistic style, but he calls them his subjects of “critique”. The interplay of the light-and-dark elements become central (and signature) to indicate Cato’s reflections on his racial identity, and embodies the dialectical relationship embedded into the ontology of Blackness. Cato revealed his discomfort towards the language, as it has failed to reflect the complexities of his experience and identity: “I am always in conflict with the illusions of race that we’ve been given or a so-called ‘Black experience’, and being mixed-race has amplified that for me. But I do revel in the beauty of the culture, I always yearn for it.” Art, then, becomes a way for Cato to forge a language of his own.

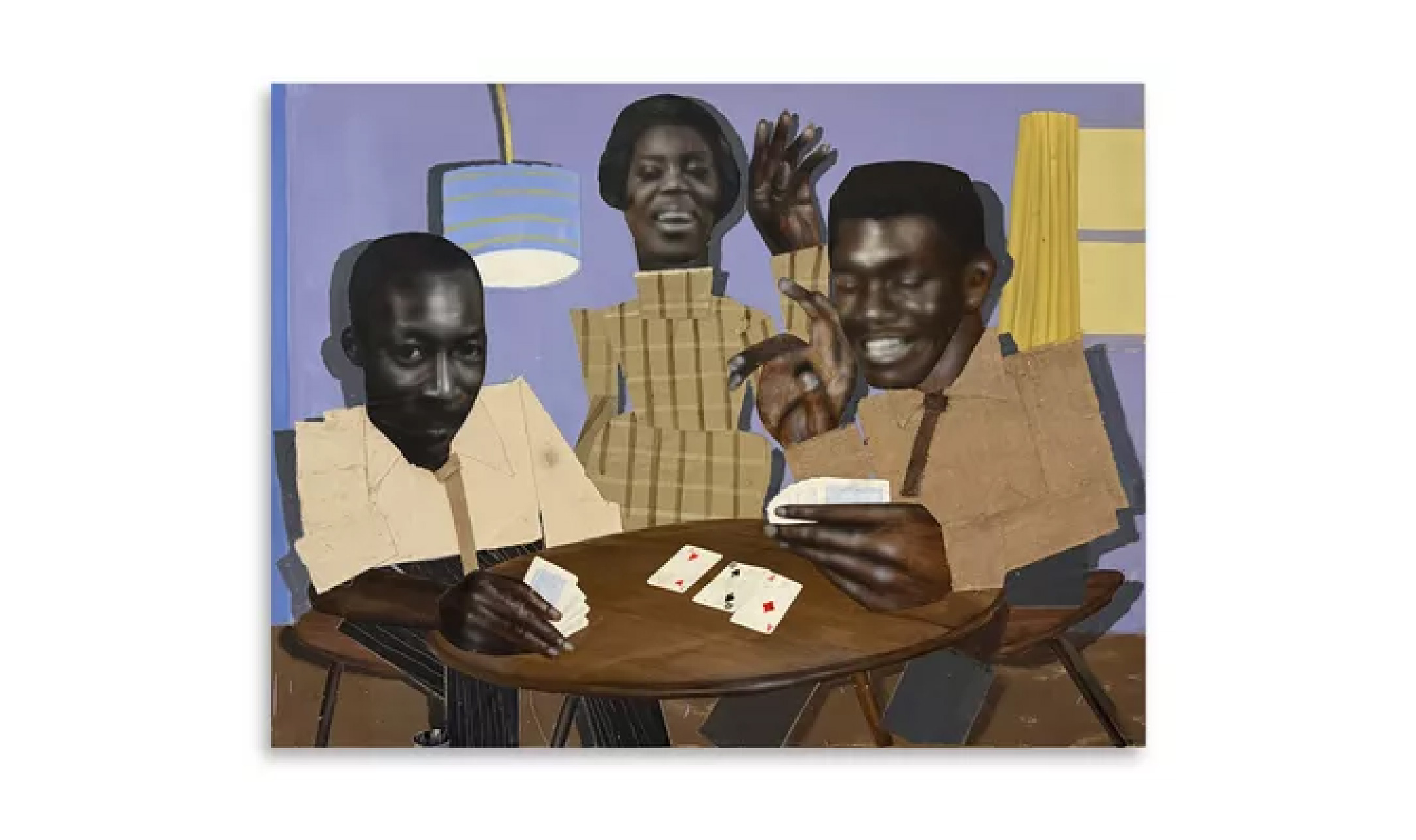

In attempting to form a visual language that is intimate to his experience, he cites Romare Bearden and Kerry James Marshall as sources of his inspiration. The creation of a Black subject to anchor Cato’s paintings is derived from Marshall, and according to writer Yaya Bey, Cato’s reference (of Marshall) comes as “no surprise”, as it is visibly apparent that they share a practice that centres on a “mastered technique, giving the viewer a foundation on which to view scenes of Black life.” Cato has always held his masters with great reverence, but also humour, describing his borrowing as affectionate theft. Of Bearden, he states: “Romare Bearden is famously known for saying ‘All art is made from other art, so I feel like I could rip him off and have his blessing.” He proudly wears Bearden’s style on his sleeve (or canvas) through his layered compositions that merges collage and painting, endowing an almost mosaic-like effect.

All in all, Cato stands firmly in his own right, while also emerging as an extension of the community that shapes him. His work reminds us that there is no singular way to articulate Blackness—and to reduce it to a fixed visual code or aesthetic system is to overlook the richness and complexity of their lineage. Instead, Cato’s practice urges us to see the artist as inseparable from their community, and their work stands not just as self-expression, but as a vessel—carrying forward the cultural memory, influence, and spirit that precedes them.