Katsuhiro Otomo Behind His Magnum Opus “Akira”

Katsuhiro Otomo was born on April 14, 1954, in Miyagi Prefecture, Japan. Growing up in a rural area with little entertainment, he spent much of his time reading manga. He developed his interest by tracing shōnen manga such as Tetsuwan Atom (Astro Boy) and Tetsujin 28-go, which became major inspirations throughout his career. When he began working as an illustrator and manga artist in the late 1970s, he aimed to recreate the excitement he felt as a child through science fiction stories.

Much of Otomo’s work leans into science fiction, partly because the genre was relatively niche in the manga world when he started. He debuted in 1973 with “A Gun Report,” a manga adaptation of Prosper Mérimée’s short story “Mateo Falcone.” He went on to produce various short works for manga magazines, gradually building his reputation. In 1979, Katsuhiro Otomo wrote and illustrated Fireball, an unfinished science fiction manga that laid the thematic groundwork for his later works. A year later, he released Dōmu, a story about psychic conflict in a housing complex, which won the Nihon SF Taisho Award and the Seiun Award. He also collaborated with Toshihiko Yahagi on Kibun wa mō Sensō, a fictional war drama between China and the Soviet Union, and revisited it decades later in a sequel.

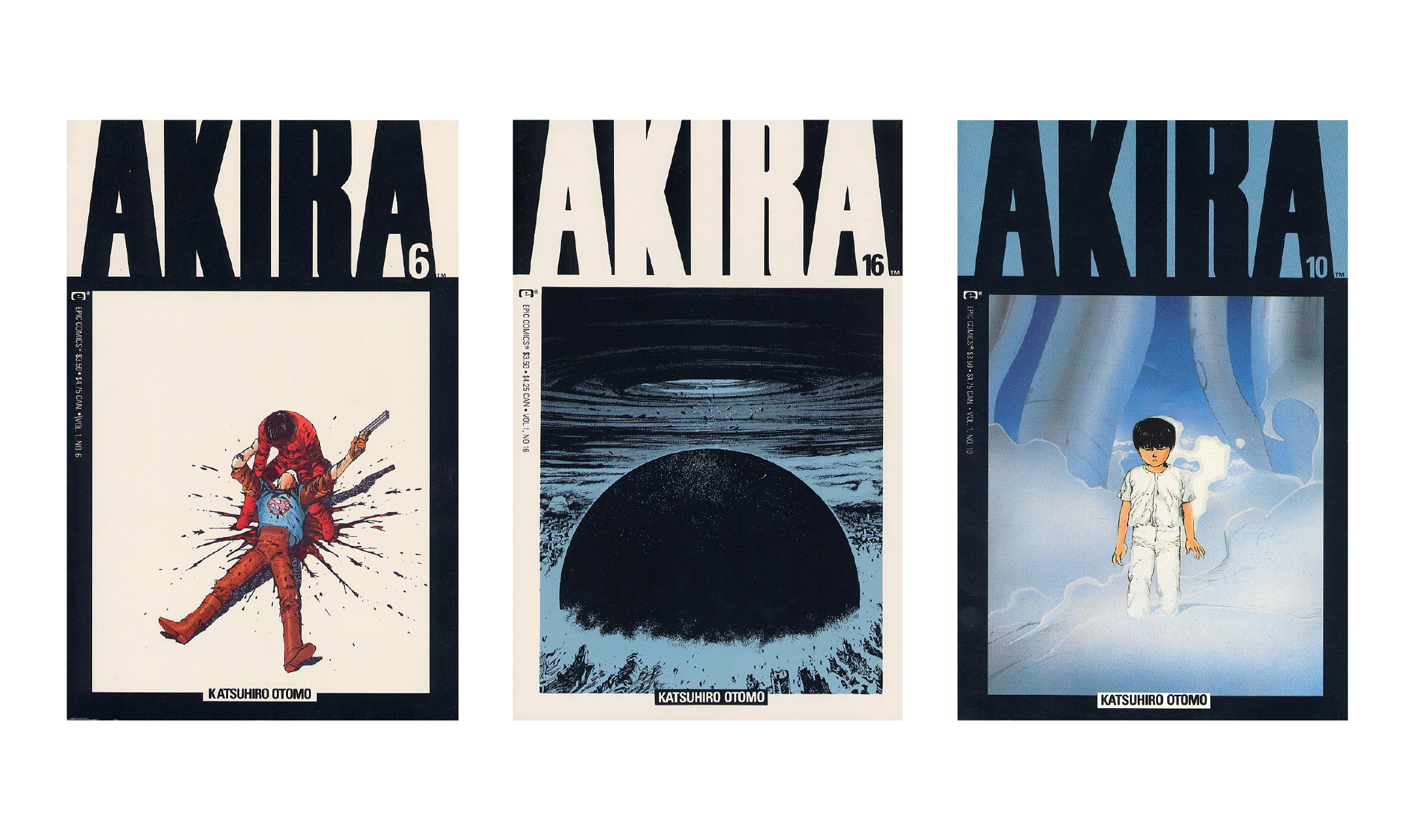

Otomo continued creating short stories, including A Farewell to Weapons (1981). In 1982, he began work on the project that would define his career: Akira. Initially planned as a ten-chapter story, it expanded into more than 2,000 pages serialized over eight years in Young Magazine. Its success brought Otomo international attention, especially after the animated film adaptation was released in 1988, also directed by Otomo.

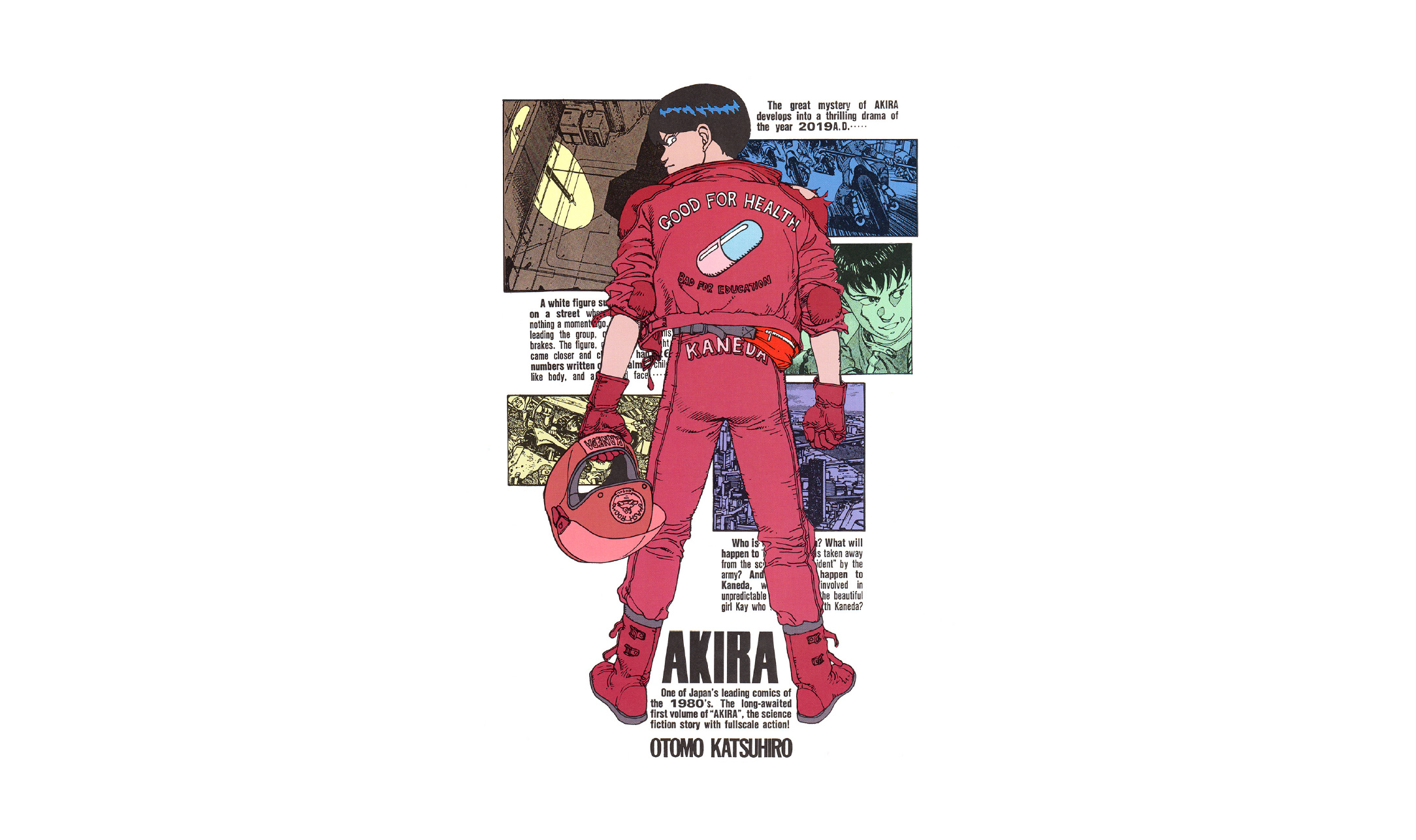

Akira portrays Neo-Tokyo, a post-catastrophe city populated by biker gangs, military experiments, and political unrest. Otomo said the story reflected his own teenage years, set against an uncertain, volatile future. He projected aspects of himself into the characters of Tetsuo and Kaneda. Although the story evolved over time, he had planned the broader structure from the beginning, determined not to repeat the unfinished fate of Fireball.

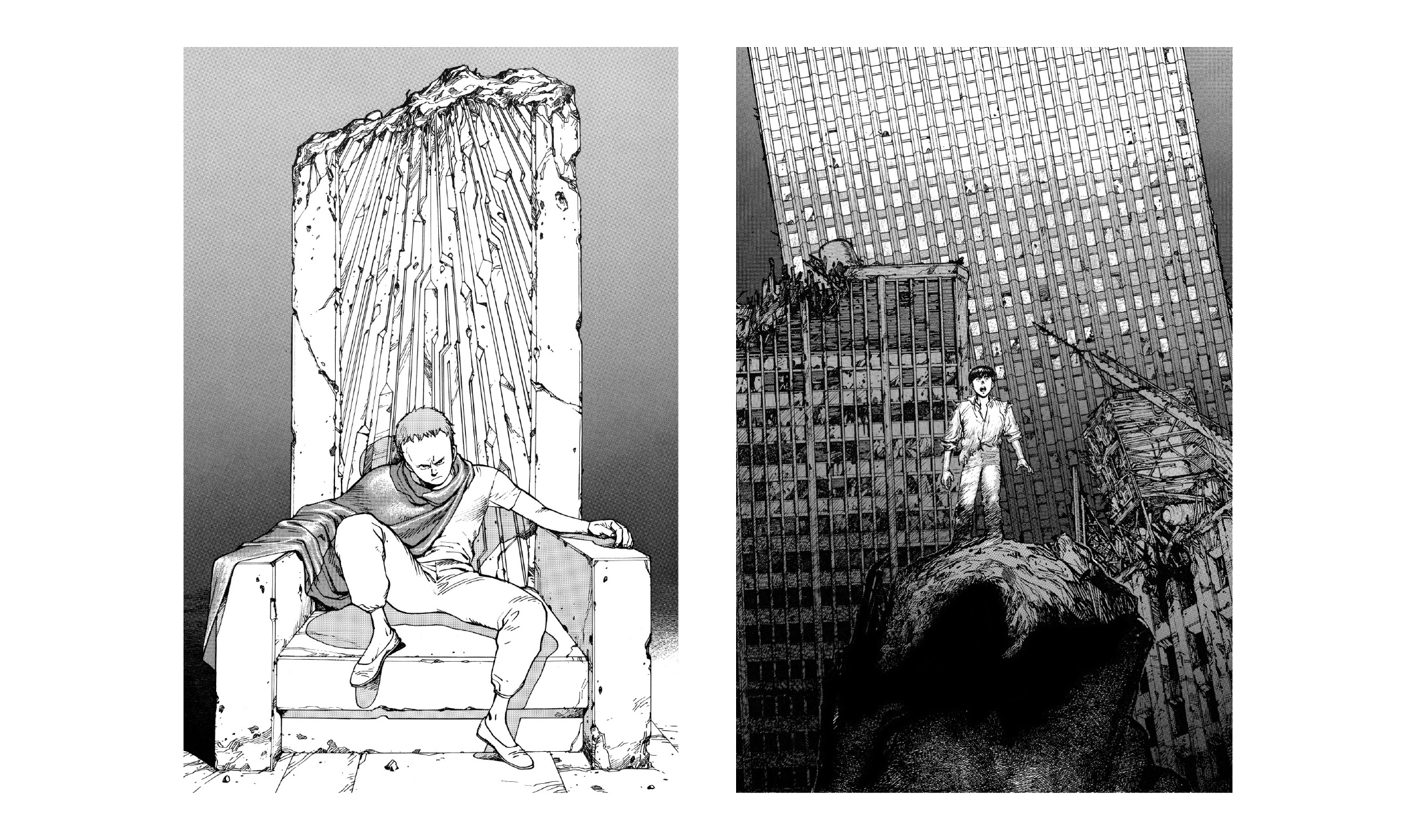

When drawing Akira, Otomo emphasized narrative speed and visual impact. He wanted readers to rush through scenes but pause at key moments. Every panel was carefully designed. He illustrated the destruction of Neo-Tokyo using manual cross-hatching, resisting editorial suggestions to simplify the page, insisting it represented the loss of millions of lives.

Akira drew inspiration from Tetsujin 28-go, particularly in its postwar themes. In an interview with Ollie Barder, Otomo explained that he embedded the number 28 into the character Akira as a direct homage. “The main plot of Akira is about the ultimate weapon developed during wartime and discovered in a time of peace,” he said. “If you know Tetsujin 28-go, then it’s the same overarching story.”

Otomo’s approach combined fantasy and realism. He reconstructed elements from late Shōwa-era Japan—Olympic preparations, student protests of the 1960s, and rapid infrastructure development—to build a believable fictional world. He avoided drawing the same face twice and based characters on close friends. His attention to urban detail and architecture became a signature, which he credited to a kind of internal mantra guiding his hand. Visually, he was influenced by illustrators Yokoo Tadanori and Isaka Yoshitaro. This gave his art a fresh, illustrative feel compared to classic manga styles.

Alongside his distinctive character design, Otomo is also recognized for his skill in mecha design, as seen in Farewell to Weapons. He cited Studio Nue and designers like Kazutaka Miyatake and Naoyuki Kato as major influences. “At that time, there weren’t any serious sci-fi manga—only comedic ones like Doraemon. I wanted to change that and do something more realistic and believable,” he said. Otomo also referenced 2001: A Space Odyssey as a major influence. “All my influences mix together… I digest a lot of different things, and ideas tend to come from that.” He named Takashi Watabe and Makoto Kobayashi among his favorite mecha designers, along with the mecha from Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Otomo rarely used computers, believing that the magic of hand-drawn images couldn’t be replicated digitally. Akira was produced under tight deadlines. He completed 20 pages per week, drawing directly on final paper without drafts. His assistants supported background detailing and screentone finishing. Despite a high price point, the first print of the manga sold over 300,000 copies.

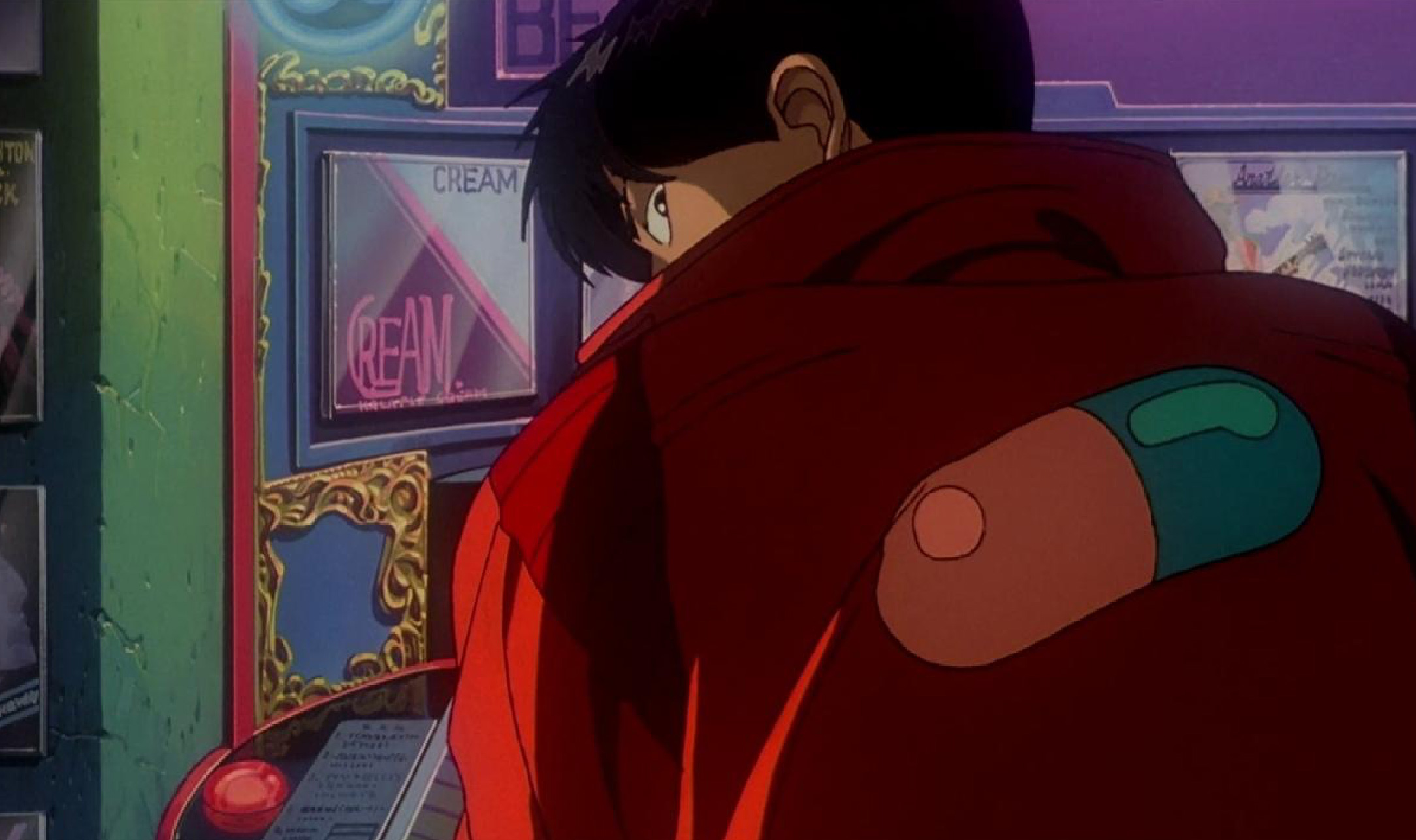

Although Otomo initially had no plans to adapt Akira into animation, he eventually agreed on the condition that he retained full creative control. The film was produced by TMS Entertainment and released by Toho in Japan on July 16, 1988. Despite Akira becoming a landmark work in his career, Otomo was disappointed when he saw the first cut. “The first part was good, but the quality dropped in the second half due to time and budget limits,” he recalled. The film had over 2,000 animation cuts, overwhelming the team. There weren’t enough animators, forcing overtime and compromises. Some of the animation had to be outsourced overseas, which he felt hurt the final product. Still, Akira remains one of the most acclaimed works of animated and science fiction cinema.

After Akira, Otomo continued working in film, directing works such as Memories and Steamboy. He said filmmaking gave him a sense of collaborative joy that solo manga work could not. Even so, he remains open to returning to manga if the time and motivation align.