Jules Chéret: The Legacy of Belle Époque and the Poster Design Revolution

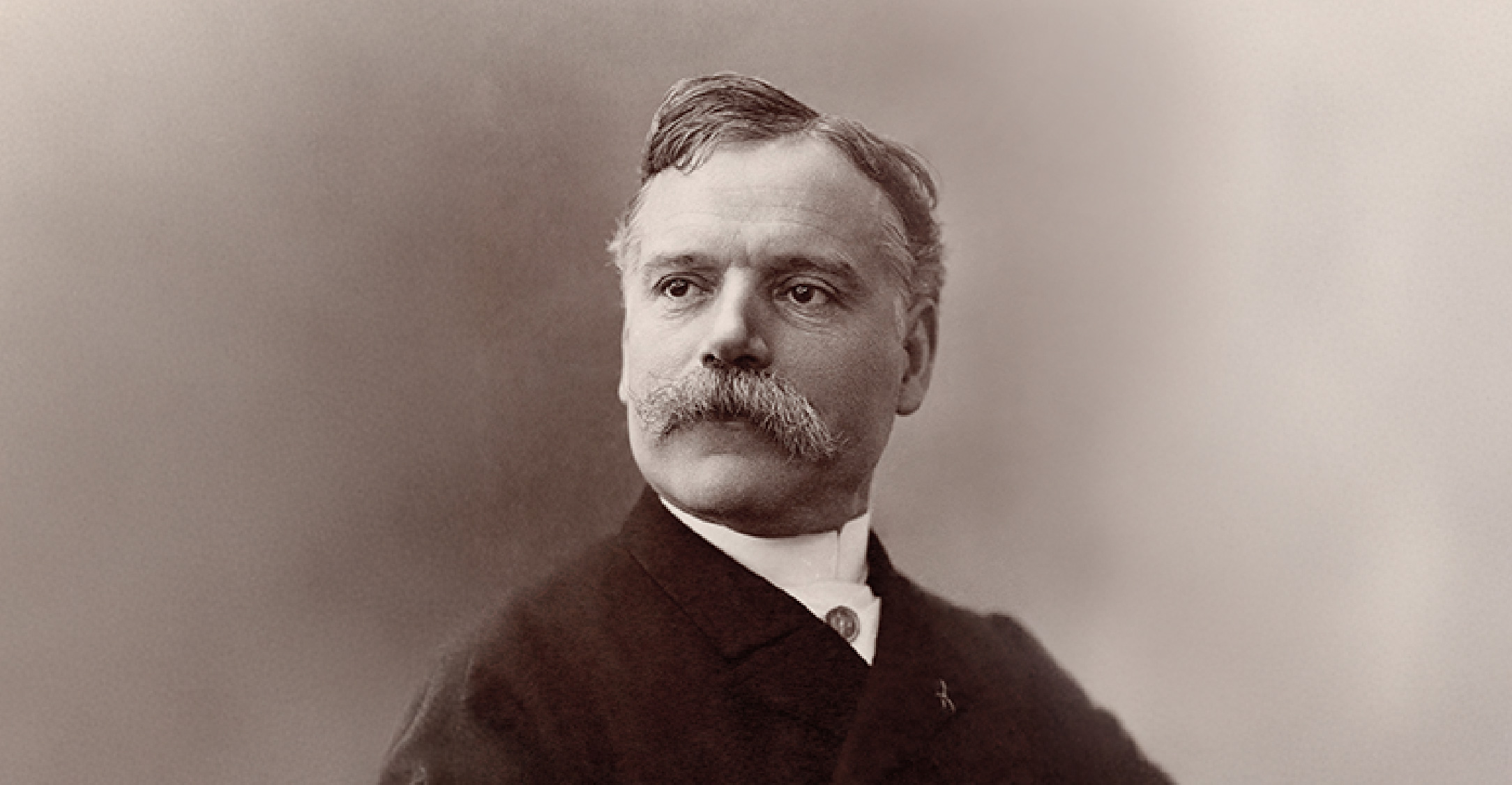

Jules Chéret was a key figure in the turning point of poster design in 19th-century Paris. Rather than merely serving as a means of communication, posters became collectible items—a form of modern art that became a legacy of the Belle Époque.

The history of posters dates back to black-and-white flyers in the 1600s, which evolved alongside the advent of the printing press. Posters then—and still today—were used to disseminate information on a large scale: merchants advertising products in shop windows, governments calling for war, and other public announcements. Poster design heavily relied on typography. As time progressed, typefaces became larger and more decorative. The rediscovery of lithography, the process used to create many posters, became a driving force in modernizing poster design. Jules Chéret, known as the father of modern posters, revolutionized this technique.

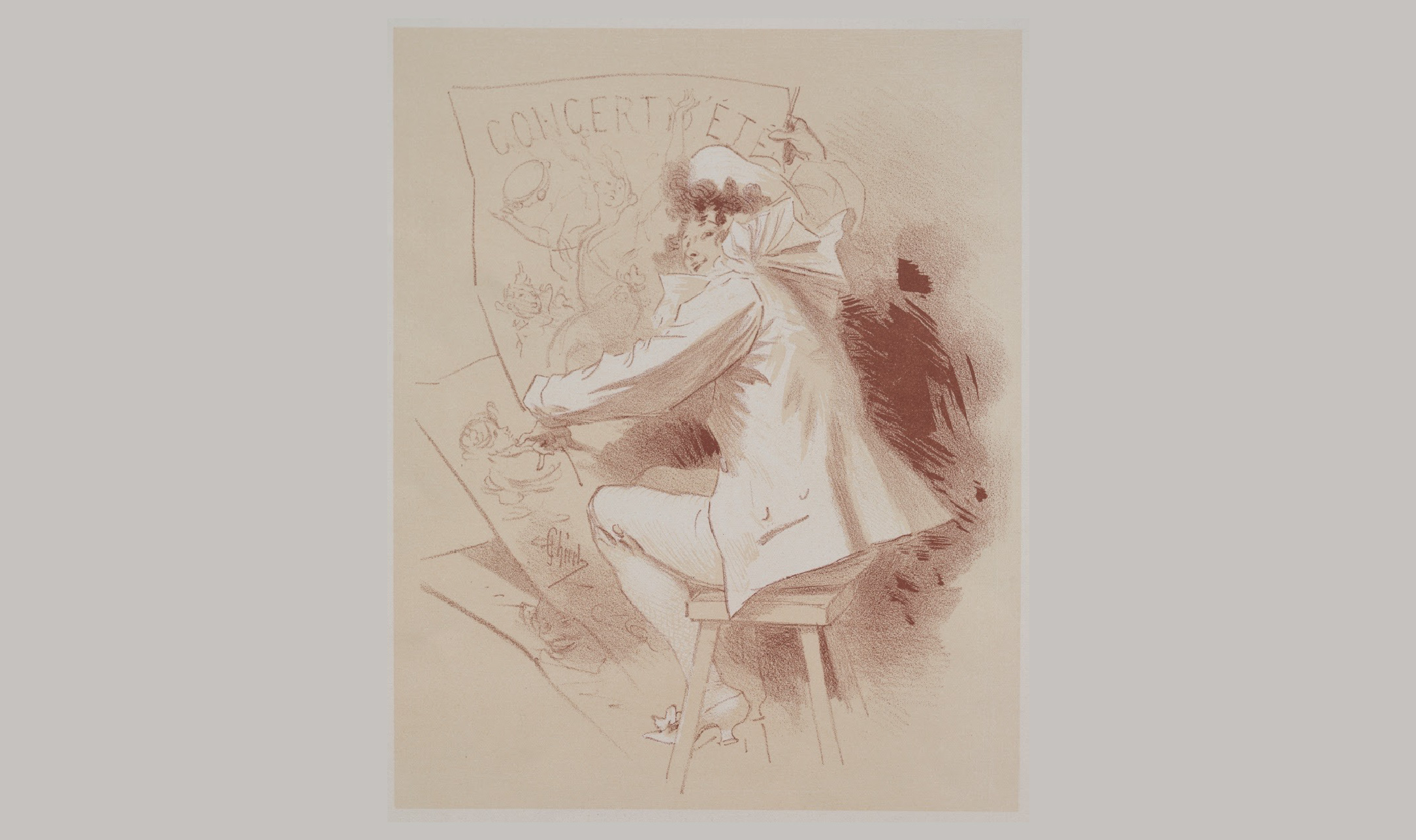

According to the Driehaus Museum, Chéret was born in 1836 into a French family of type compositors. After a brief period of studying drawing, he began training in lithography at the age of 13 while working part-time. His breakthrough in the visual arts industry came when perfume manufacturer Eugène Rimmel hired him as a designer. Not long after, he established his own lithographic printing company in Paris, firmly believing that lithography would soon replace his father’s letterpress printing industry as the dominant printing technique. Speaking of lithography, its low quality and disposable nature initially made it unworthy of artistic production. Lithographic prints were considered cheap reproductions, unlikely to be included in museum collections. The demand for lithography was solely for rapid commercial messaging, devoid of originality, boldness, or beauty.

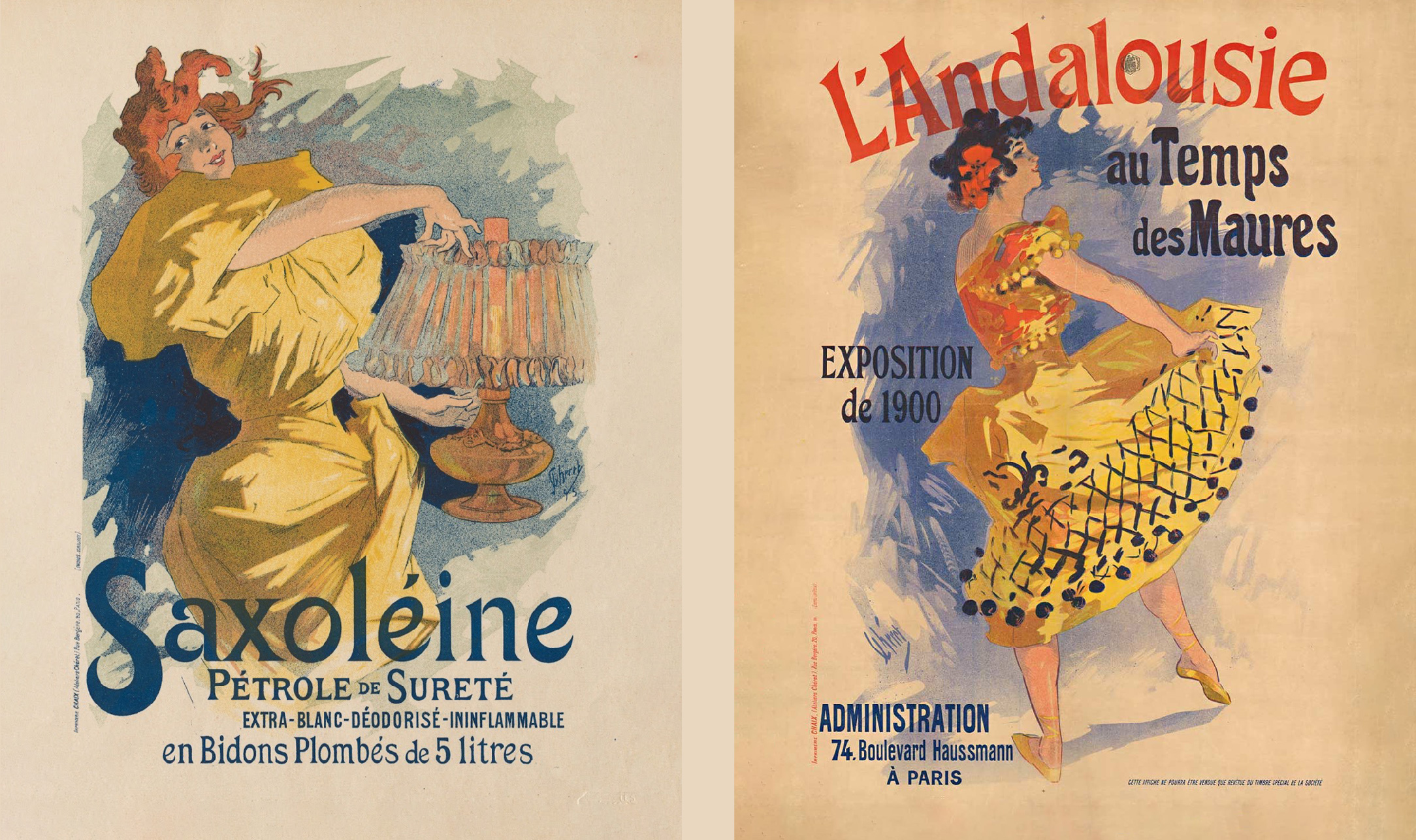

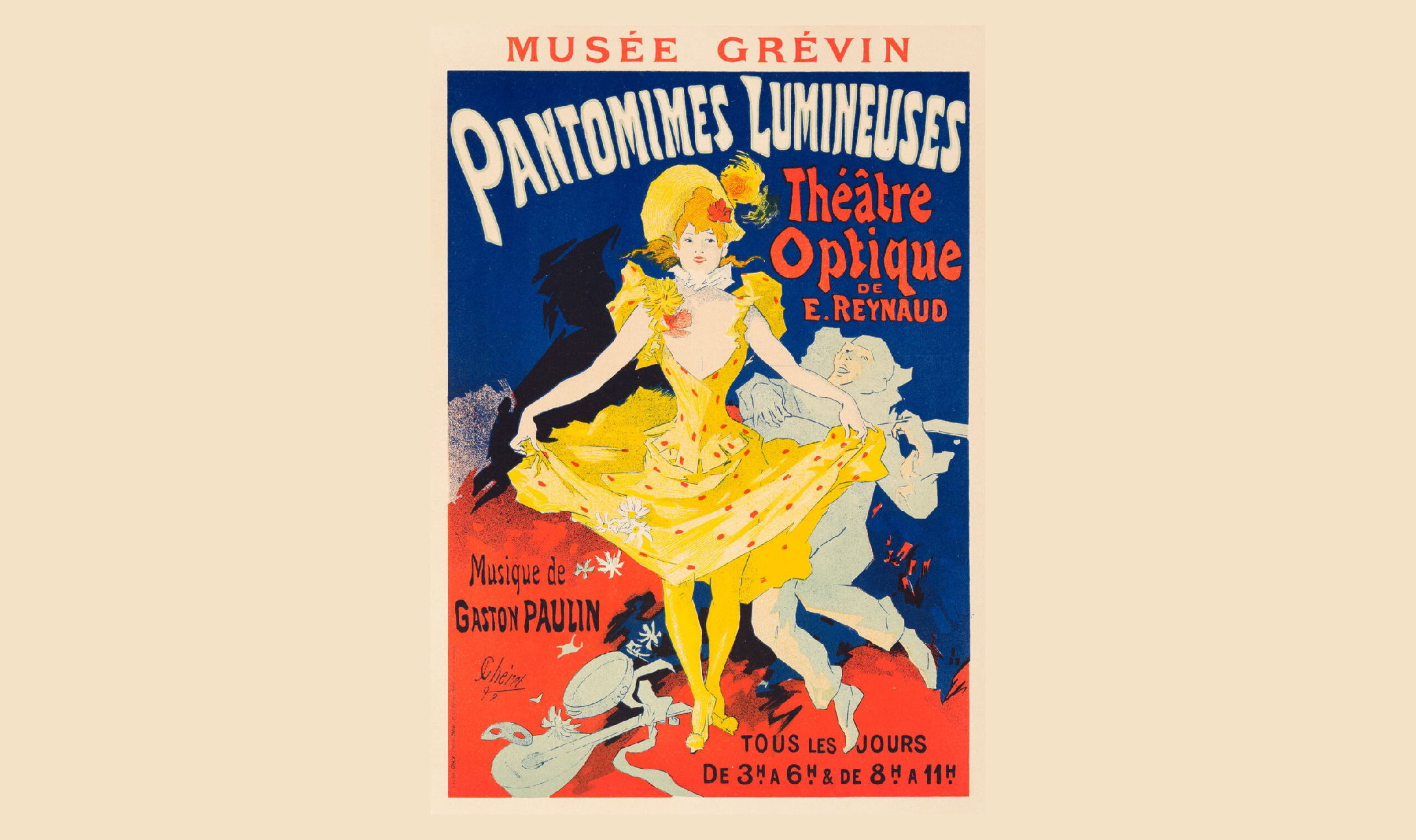

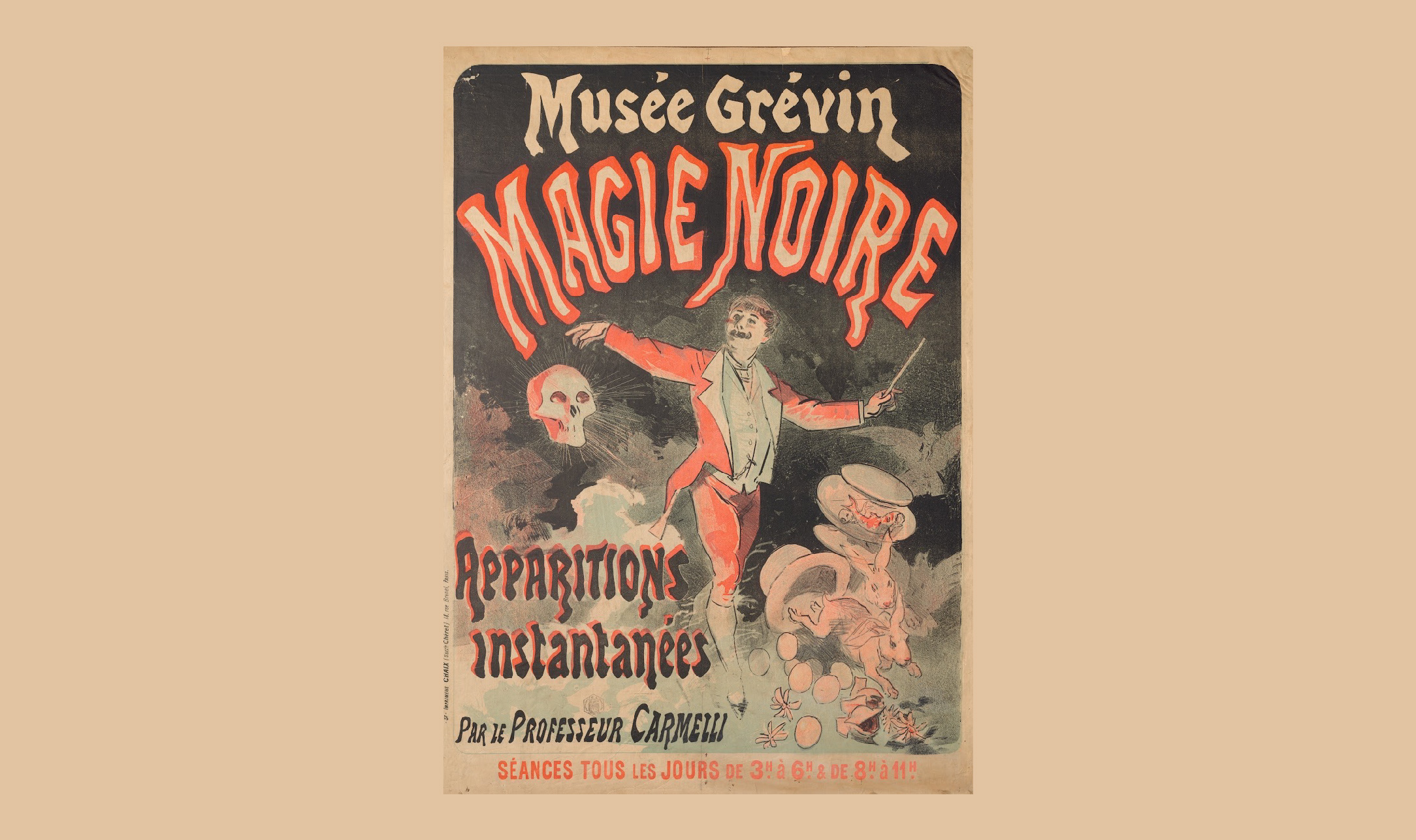

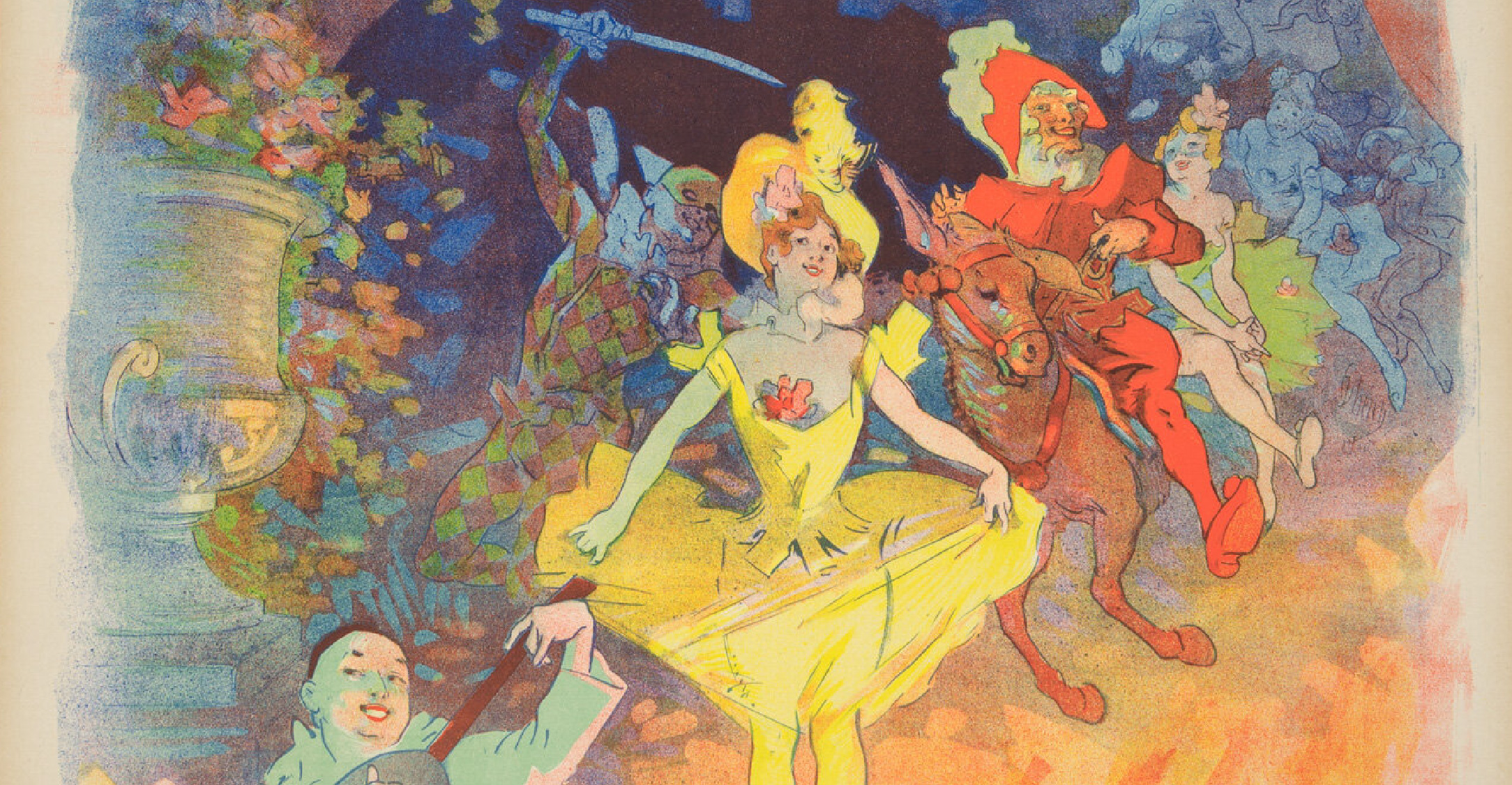

During the Belle Époque, a golden era for art and culture in Europe, Chéret radically transformed lithography to achieve an original artistic quality. Instead of being constrained by the negative stigma surrounding the technique, he harnessed it to create vibrant posters infused with a distinct French charm for various entertainment venues such as Eldorado, Olympia, Folies Bergère, Théâtre de l'Opéra, Alcazar d'Été, and Moulin Rouge. His works not only promoted performances but also a wide range of products such as beverages, perfumes, and cosmetics. In 1884, Chéret took a bold step by organizing the first-ever group exhibition of posters in art history, paving the way for their acceptance and celebration as a legitimate art form. Two years later, he published the first book on poster art. Chéret also collaborated with printing houses that catered to collectors eager to own posters as part of their personal collections.

Beyond lithographic techniques, Chéret made significant contributions to poster design aesthetics. He designed his typefaces, leveraging the advantages of lithography over letterpress printing, where artists could draw directly onto the printing surface. He also minimized the amount of text in his posters, relying instead on illustrations as the primary medium for communication. Additionally, Chéret simplified the chromolithographic process by using only three primary colors—red, yellow, and blue—with each color printed from a separate stone. By making these colors semi-transparent, he was able to layer them to create new hues. In every poster he designed, Chéret employed dynamic brushstrokes, crosshatching, stippling, soft watercolor-like washes, and combinations of flat colors. His fellow chromolithographer, André Mellerio, praised Chéret's work, calling colored posters "the defining art of our era," marking a major shift in the world of design.

Another significant contribution by Chéret was his depiction of women in posters. Previously, female representations in art were often confined to specific stereotypes. However, Chéret’s creative innovations introduced lively, joyfully expressive women in somewhat revealing attire for that era, later known as Chérettes. His illustrations of women were inspired by figures from the Rococo period, a splendid era in France immortalized by artists such as Jean-Honoré Fragonard and Jean-Antoine Watteau. With their captivating charm, the Chérettes embodied various aspects of Parisian entertainment—from theaters and concert halls to musicians. These posters not only functioned as advertisements but also captured an alluring lifestyle, reinforcing Paris as a hub of culture and entertainment.

As posters gained recognition as a respected art form, in 1895 Chéret launched the Maîtres de l'Affiche collection, an art publication featuring smaller-scale reproductions of the finest works by 97 Parisian artists. This collection not only showcased his own work but also promoted other artists, enriching the world of poster art during the Belle Époque. Over his career, Chéret created more than a thousand posters. One critic once remarked, "There is a thousand times more talent in the smallest Chéret poster than in most paintings on the walls of the Salon in Paris." Chéret was frequently imitated, and his work inspired an entire generation of artists who further developed his approach. One of those artists was Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who, as a tribute to Chéret, always sent him copies of his own posters.

In his later years, Chéret moved to Nice, where he spent the remainder of his life until passing away at the age of 96. His artistic legacy endures, and his posters remain prized collections in museums and among art collectors worldwide. Chéret’s work not only revolutionized advertising but also influenced the evolution of graphic art and modern design to this day.