An Ode to Miyazaki’s Humanity: Tethering the Fragile Line between Homage and Harm

Written by Sabrina Citra

In the documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, we are met with Hayao Miyazaki who stands beside a window. He ushers the crew to come close and unravels a landscape that is seemingly ordinary. Pointing towards a man watering his plants, he said, “See him watering his plants? He has no idea we’re watching him.” He then paused to imagine a thought that connected the different structures constituting the skyline–a house covered in ivy, a rooftop, a blue and green wall, a cable line, and a pipe–and articulated: “See that house with all the ivy on it? From that rooftop, what if you leapt onto the next rooftop, dashed over to that blue and green wall, jumped up and climbed the pipe, ran across the roof, and jumped to the next? You can, in animation.”

For Miyazaki, people-watching is an exercise of finding inspiration and imagination by bearing witness to the life that unfolds around him. Positioning himself as a distant stranger grants him the ability to locate and assign meaning towards whatever sight or scene he deems of interest and allows for stories to emerge naturally. He, then, continues his narration: “Suddenly, there in your humdrum town is a magical movie. Isn’t it fun to see things that way? Feels like you could go somewhere far beyond.”

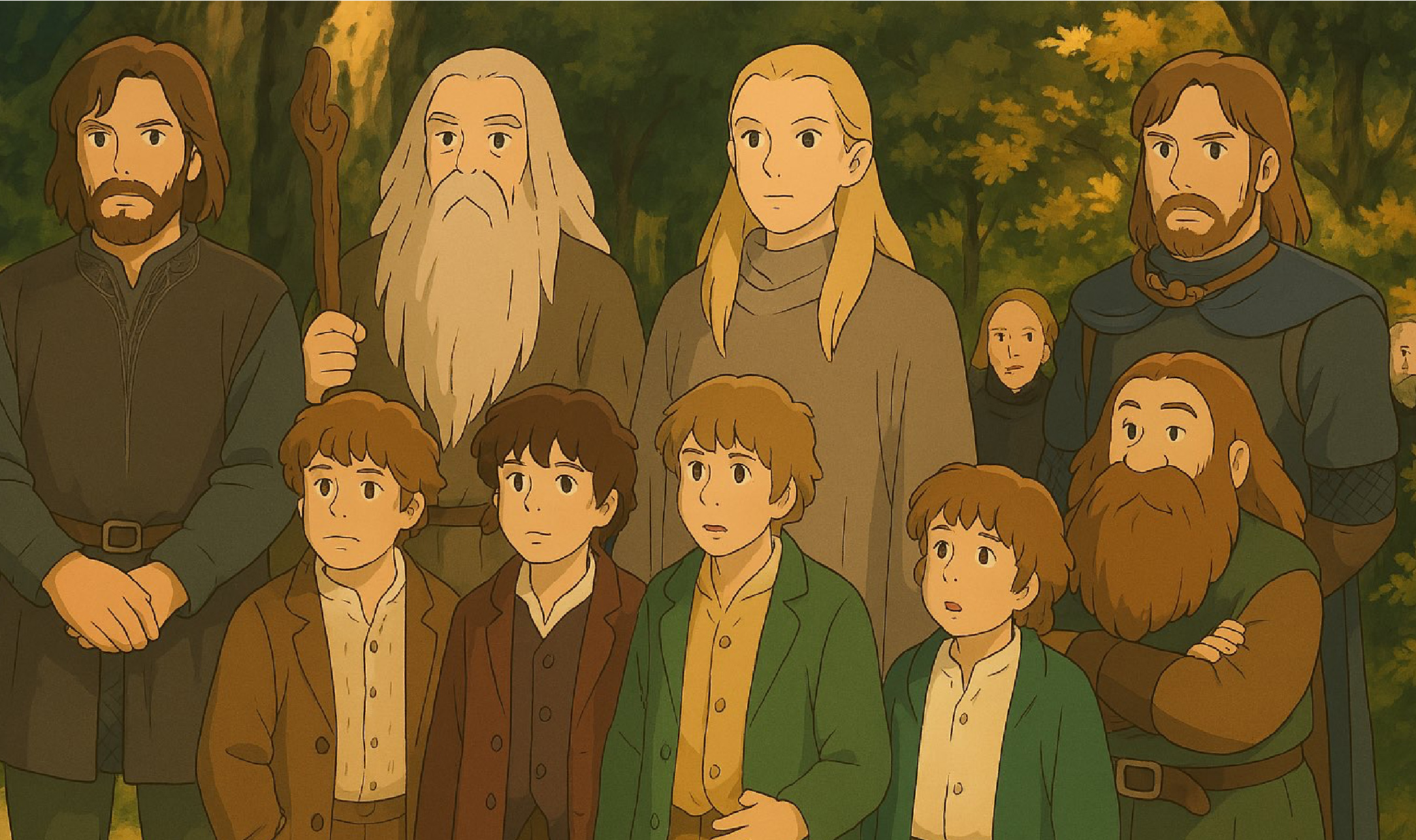

We witness the ease that marks the beginning of a creative process simply by responding towards the conditions of living. Miyazaki exhibits that storytelling emerges from recognising humanity by tending towards the realities of life that bind us. He addresses this by centring crisis as a thread to his filmography and establishes each Ghibli film as a story of survival, where each protagonist must respond to the difficulty in their conditions of living- from ‘rebuilding’ a life amidst the repercussions of the Japanese war in Grave of the Fireflies, protecting land amidst the ecological crises in Princess Mononoke, saving misunderstood parents in Spirited Away to wrestling with the burden of legacy in the Boy and the Heron- and remain resilient. The intimacy that is felt upon experiencing these stories becomes natural as they are rooted in the familiar truths of (our) existence. In effect, we build kinship with the characters across the Studio Ghibli universe as we share the feelings of despair, exhaustion, joy, and even hopefulness that constitute the experience of being human.

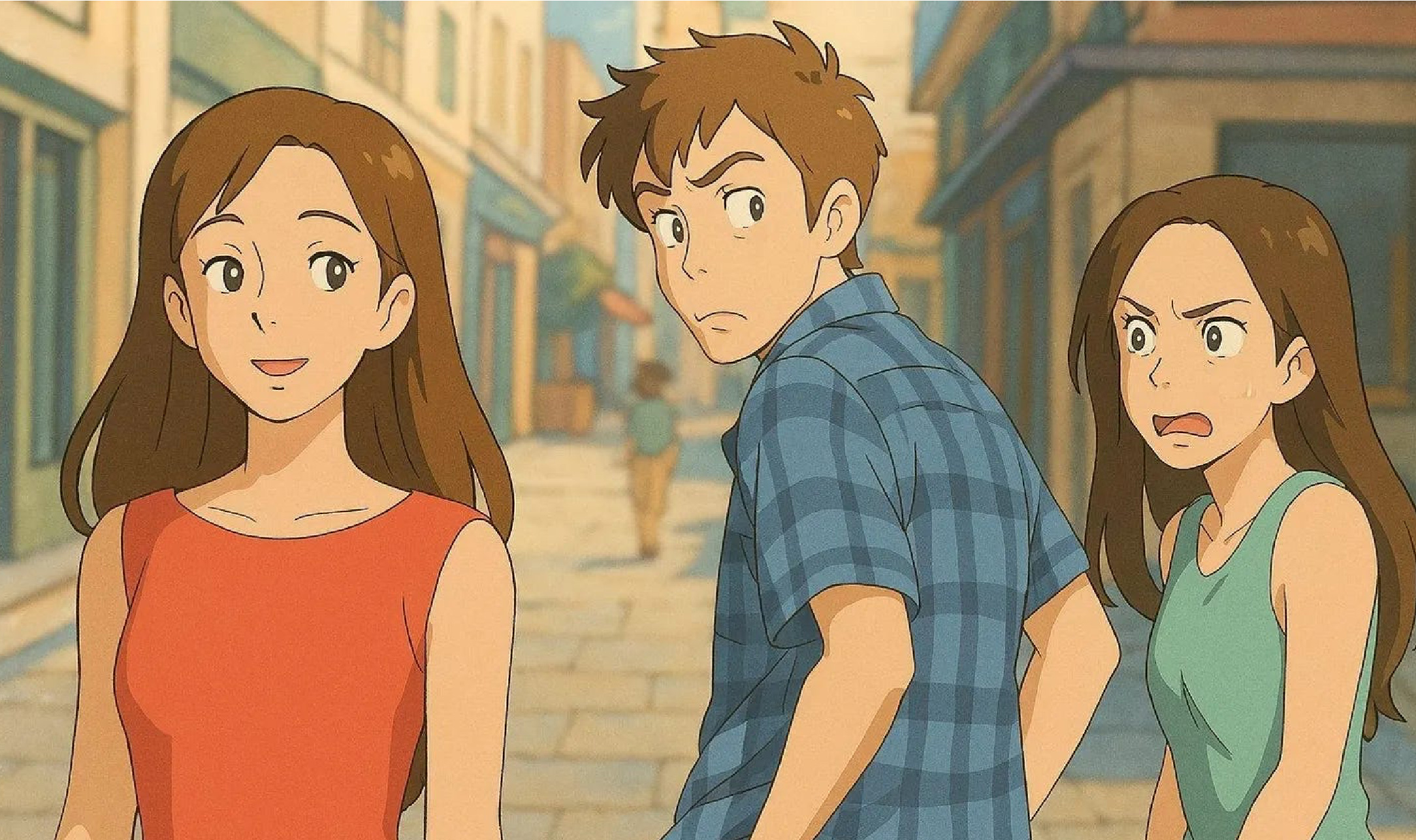

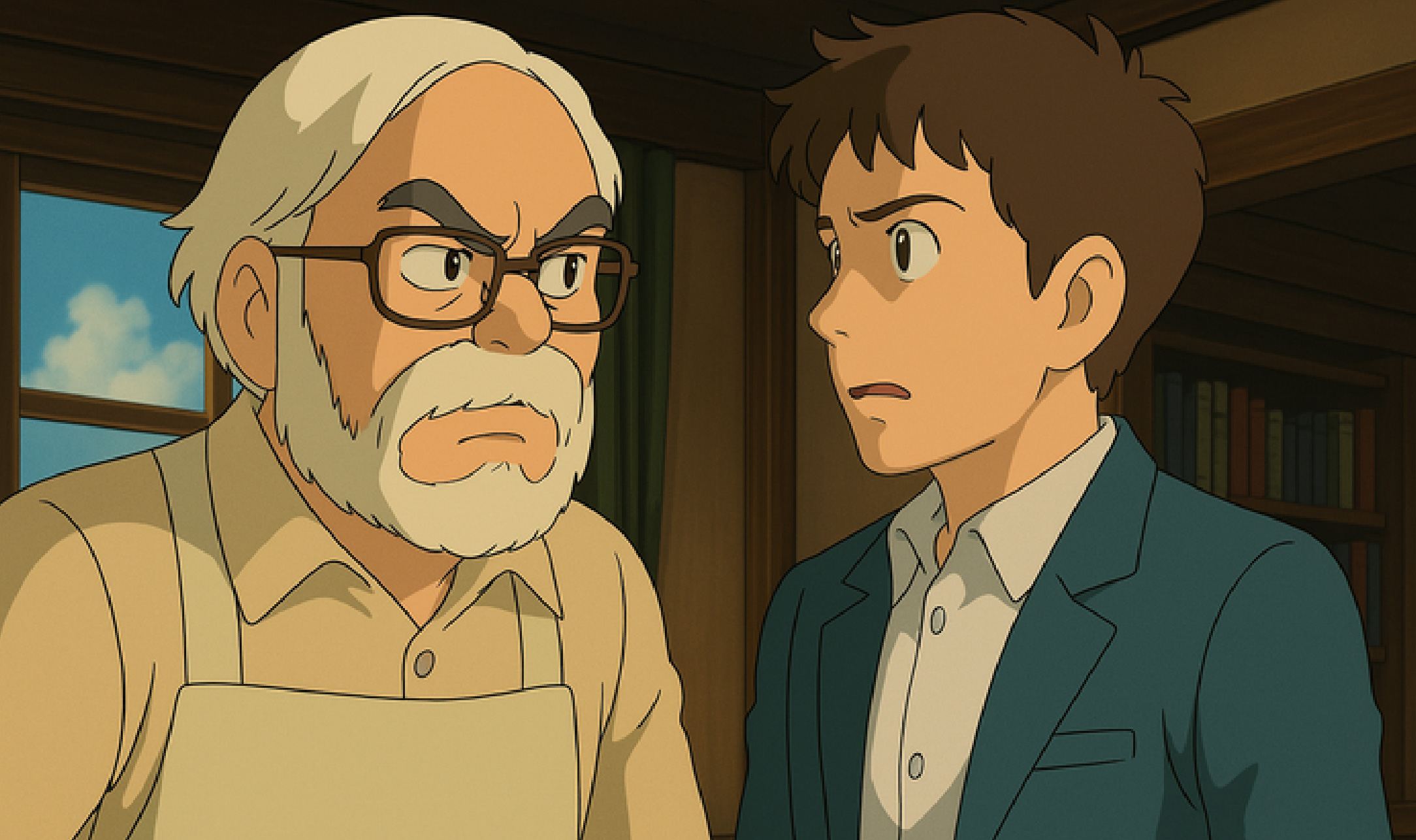

Imbuing humanity into his work automates a beauty in Studio Ghibli’s animation. It is the way that the characters and landscapes are drawn that evokes a sense of human-ness that is not only aesthetically pleasing, but also goes into the depths of our imagination. The Ghibli artistic style is incredibly distinct yet possesses variety: there are details in the orchestration of its characters and their landscape that respond towards the contexts of each world within the Ghibli universe and enabling them to coexist amongst one another.

Tending to detail requires labour amongst creators, which goes beyond Miyazaki’s capacity as a visionary and requires an ensemble of collaborators that include actors, animators, composers, producers, and technicians. We observe that Studio Ghibli is driven by a shared value towards humanity, evident in each film’s ability to function as an answer towards the (relevant) conditions of life and address the crises in living that we bear.

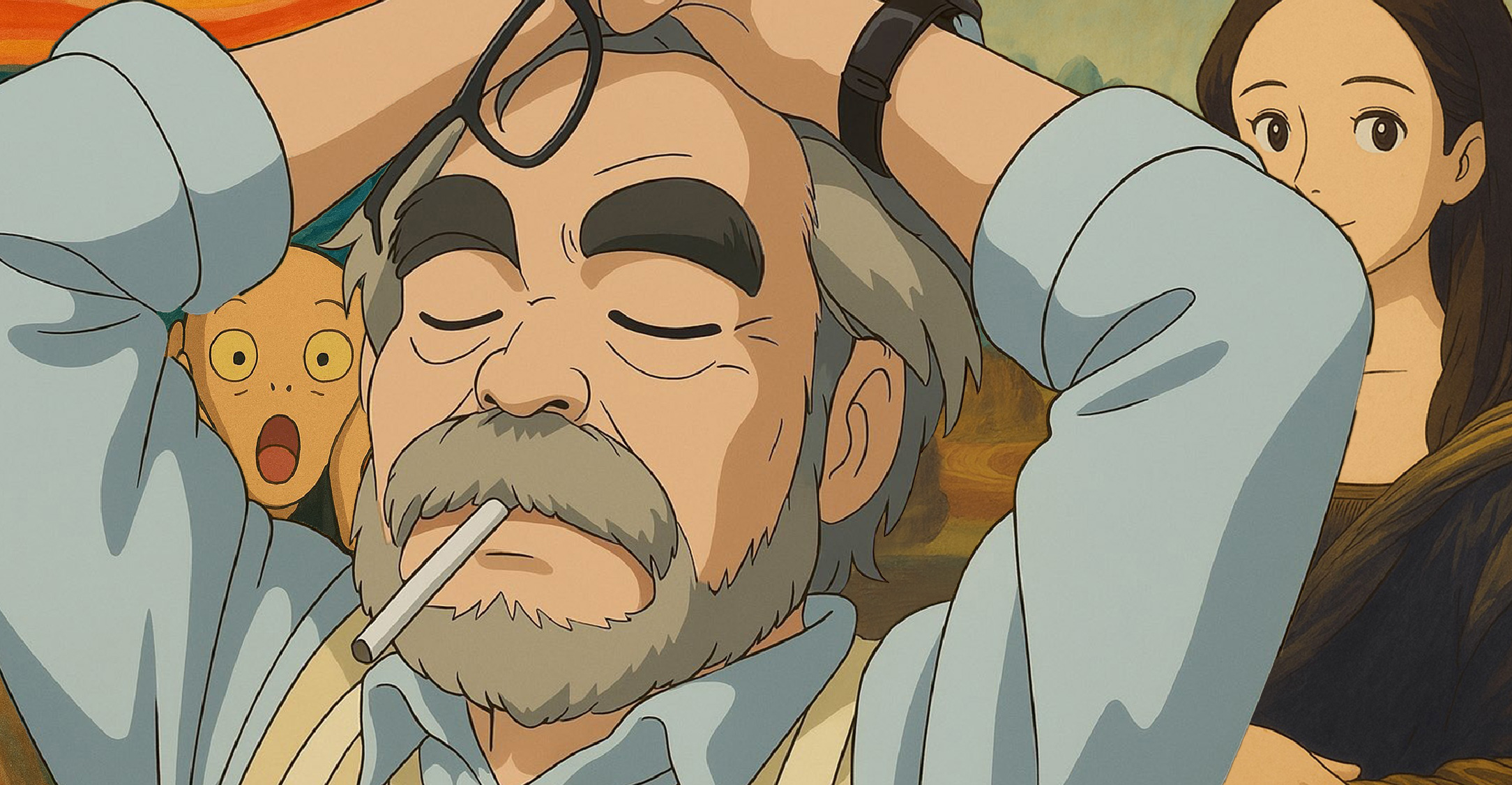

Studio Ghibli’s materialisation of humanity throughout their storytelling testifies to their commitment towards an ethical approach in creation. With that being said, it is only fair to deem the circulation of AI-generated images that mimic Ghibli’s animation style as unethical; Miyazaki himself has rejected any practices that incorporate AI into his creation, stating that “I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.”

Truthfully, we can agree that the AI-generated pictures are ‘accurate’ in their replication of Ghibli’s style, but we cannot deny the hollowness in their conception. It does not contain the beauty that is derived from the materialities constituting Studio Ghibli’s animation, as it has failed to carry the values of humanity inherent in the creative process and extend into its aestheticisation.

With that being said, we can assume that the popularity of producing Ghibli AI-generated images is due to online trends. Over the past few years, there has been a growing trend amongst the Indonesian public to post AI-generated images on Instagram, which designates a fixed procedure that requires an interaction with ChatGPT: (1) person insert a prompt in ChatGPT, (2) ChatGPT generates said image based on prompt and (3) person post said AI-generated image on Instagram. The ease of AI-generation establishes its importance as a machine of ‘creation’ that is unfortunately efficient, and this enables the banality of the use of AI across multiple contexts (i.e., in social media and the broader creative industry).

When we speak about the ‘rhythms’ of creation, there has been minimal space allowed for creatives to linger, wait, and wonder, as there is an expectation to constantly answer towards the demand for production. As Miyazaki has mentioned, the sole reliance on technology upon creation deprives us of humanity and dictates us to operate out of efficiency.

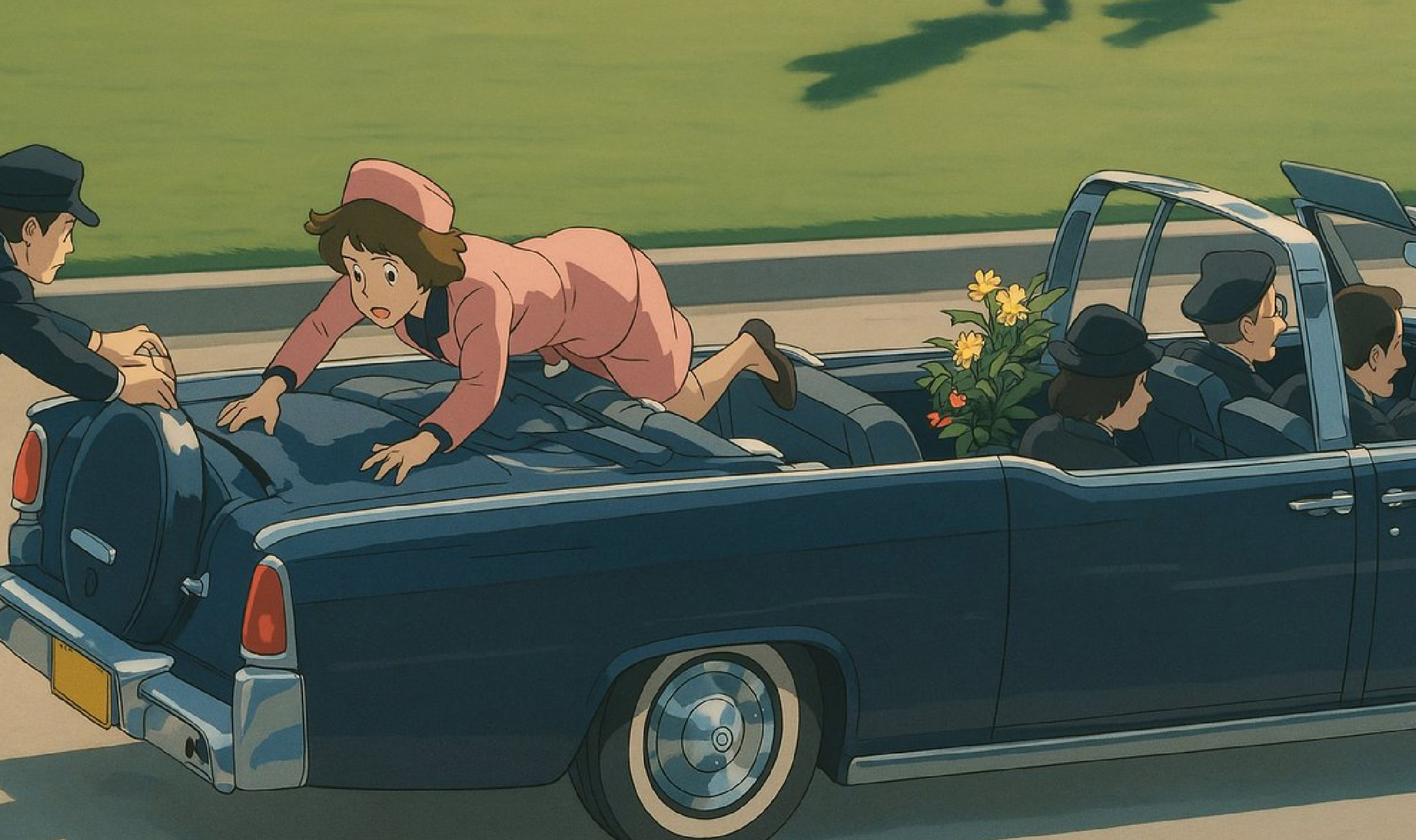

The question of humanity can be extended to consider the use of Ghibli x AI-generated images amongst the social media channels of ‘government officials’ that memeify the violences that they perpetuate: the US’ government’s portrayal of arresting immigrants and painting Donald Trump as a ‘cutesy’ figure coupled with the IDF’s (Israeli Defense Forces) attempt to sanitise their war crimes. It is apparent that there is an enabling of state officials to instrumentalise the aesthetic of Studio Ghibli to ensure the digestibility of their crimes amongst the broader public. In the spirit of humanity that Ghibli aspires to, we must reject the co-optation of Studio Ghibli’s animation to be of use in harmful contexts; as this contradicts the critique that the films have made against state violence.

With these contexts in mind, we can ask the ultimate question of can we allow for aesthetics- in the case of Studio Ghibli- to ‘belong’ to everyone?

If the ultimate goal is to insert yourself into the Ghibli universe, then it is best to approach this in a way that pays homage to Studio Ghibli’s ethics and processes of creation. To not only attempt towards replication (as we know that is what AI is capable of), but to go in the direction of offering interpretation.

This has been taken upon by the internet tradition of fan art. The reincarnation of Ghibli’s art is kept alive amongst artists, designers, and illustrators whose labour has formed the lifespan of Studio Ghibli's online fandom. We have been inspired by the fan art that is circulated online, which forms our interest in watching a Ghibli film. Fan art offers a sweet interpolation of one’s signature style that marries into the dimensions of the Studio Ghibli world–in a way, we can interpret this as an extension of Ghibli’s world-building. The nature of these fanarts is also varied and ranges from imagining their own participation as a Studio Ghibli character to the admiration (and oftentimes infatuation) towards existing characters and Miyazaki himself. Amid the Ghibli x AI incident, several illustrators have openly critiqued its use and offered their work as an ethical response against the use of an AI generator in producing art. Their work exhibits the important practice of care that is embodied by any creator who carries the intent to pay their respects to their creative elder (in this case, Miyazaki) and continue their legacy.

Upon reflection, we can arrive to conclude that the controversy with AI stems from the threat against the ‘human’ labour in creation. Miyazaki’s case explicates the machine’s capacity to not only affect the work amongst small and independent artists but also larger production houses such as Studio Ghibli. This ultimately raises the questions of can we, as creatives, go beyond the fixation to produce efficiently? Can we attempt towards repair against the systems that have been in place?

We hope to end this article with an observation that Miyazaki has made in one of his interviews when he was asked whether he worries about the future of Studio Ghibli, and to which he answered, “The future is clear. It’s going to fall apart.”