The Factory: A Space for Cultural Experimentation

The Factory was a place where art, urban lifestyle, and popular culture converged in the most intense and unexpected ways. Founded by Andy Warhol in the early 1960s, this studio was not merely a workspace, but the heart of a creative universe involving artists, poets, models, musicians, curators, writers, and even people who simply wanted to be part of something that felt important in its time. It was not a gallery, not a home, not an office, not a nightclub, but all of those at once.

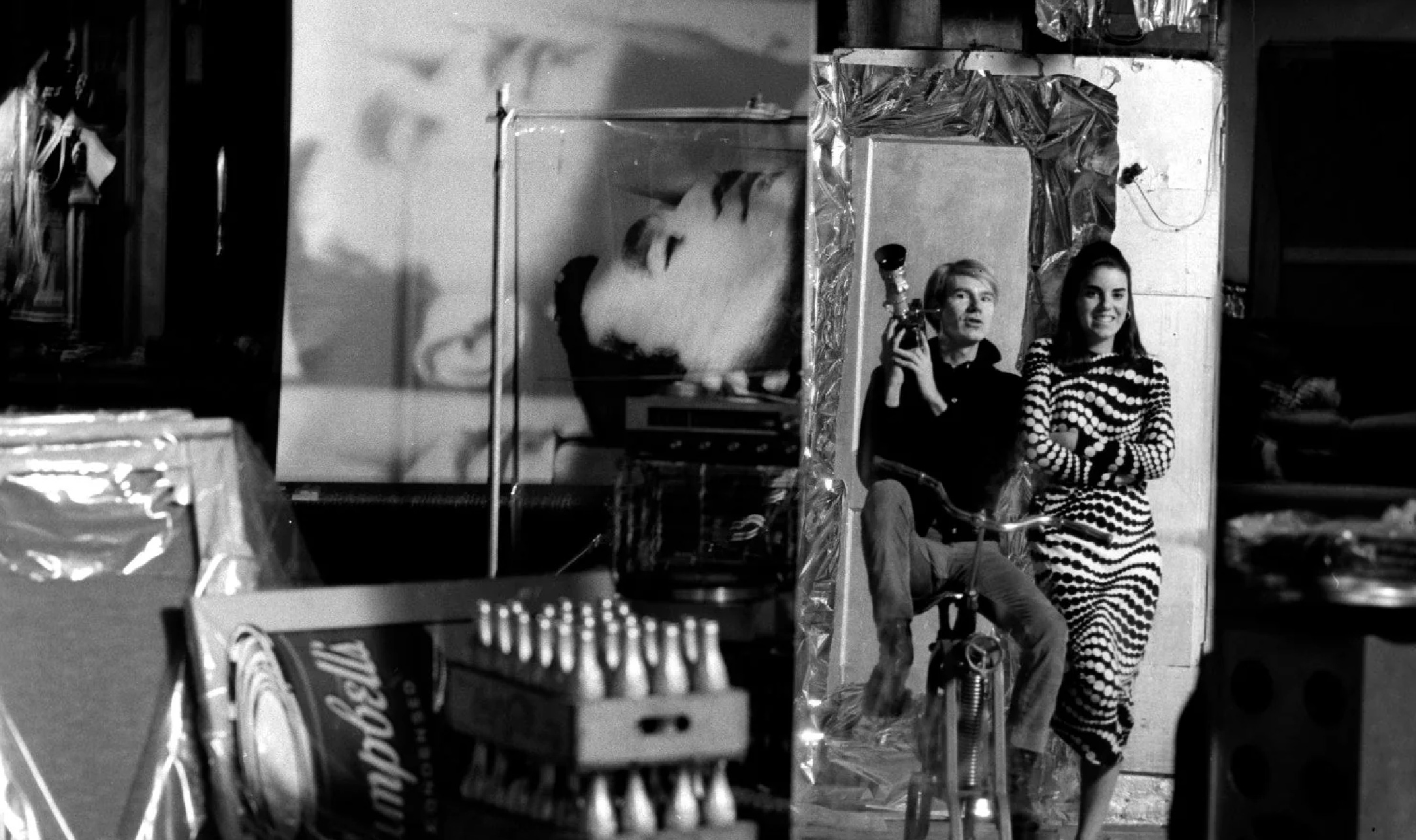

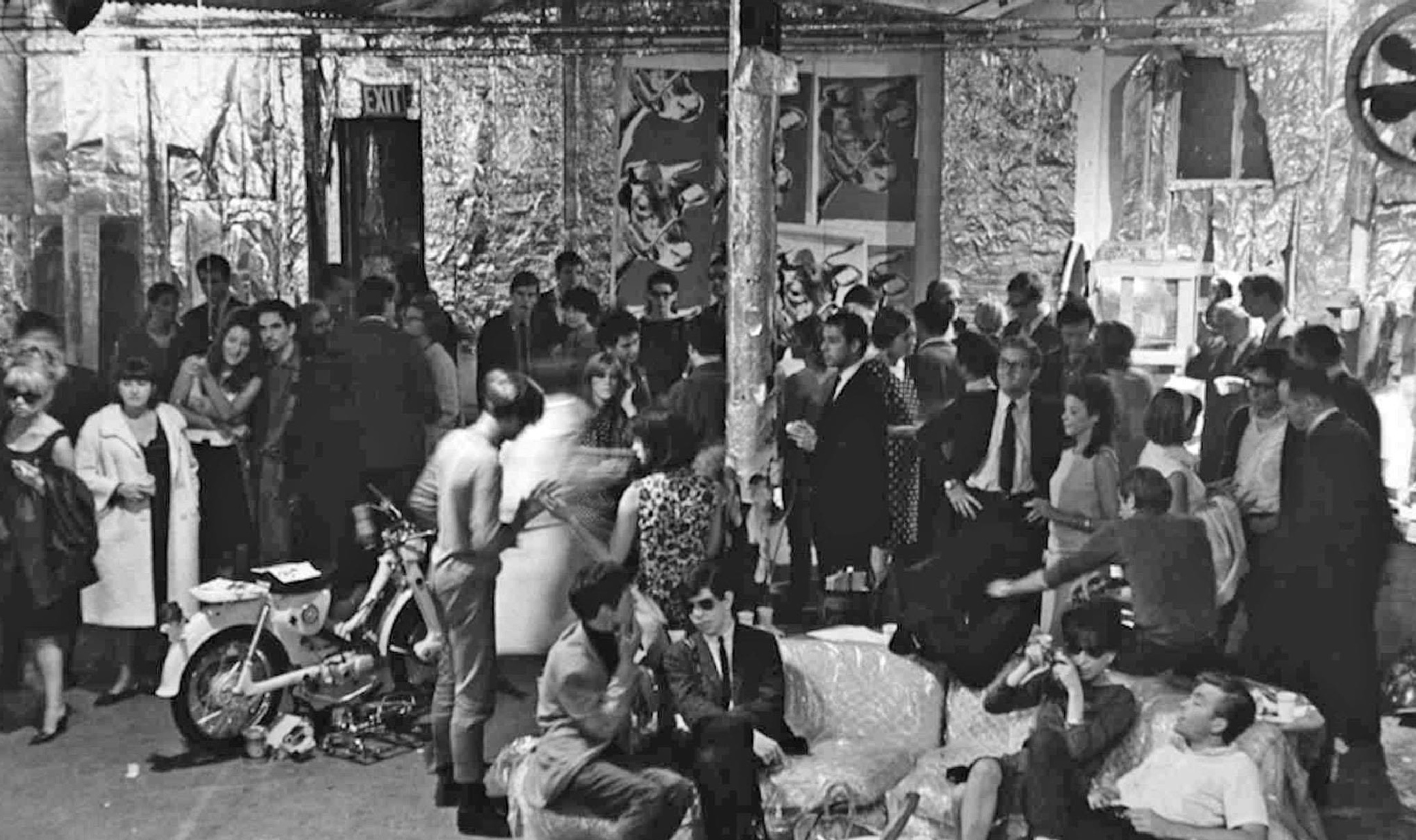

In 1963, Warhol decided to rent a space on the fourth floor of a multipurpose building at 231 East 47th Street, Manhattan. The place later became known as The Factory, partly because Warhol wanted to respond to the concept of mass production in American culture. He no longer saw art as the product of a solitary, genius artist, but as a collaborative process that could be duplicated, developed, and even industrialized. The studio was covered in aluminum foil and painted silver, creating an atmosphere that felt like a shiny, surreal space capsule.

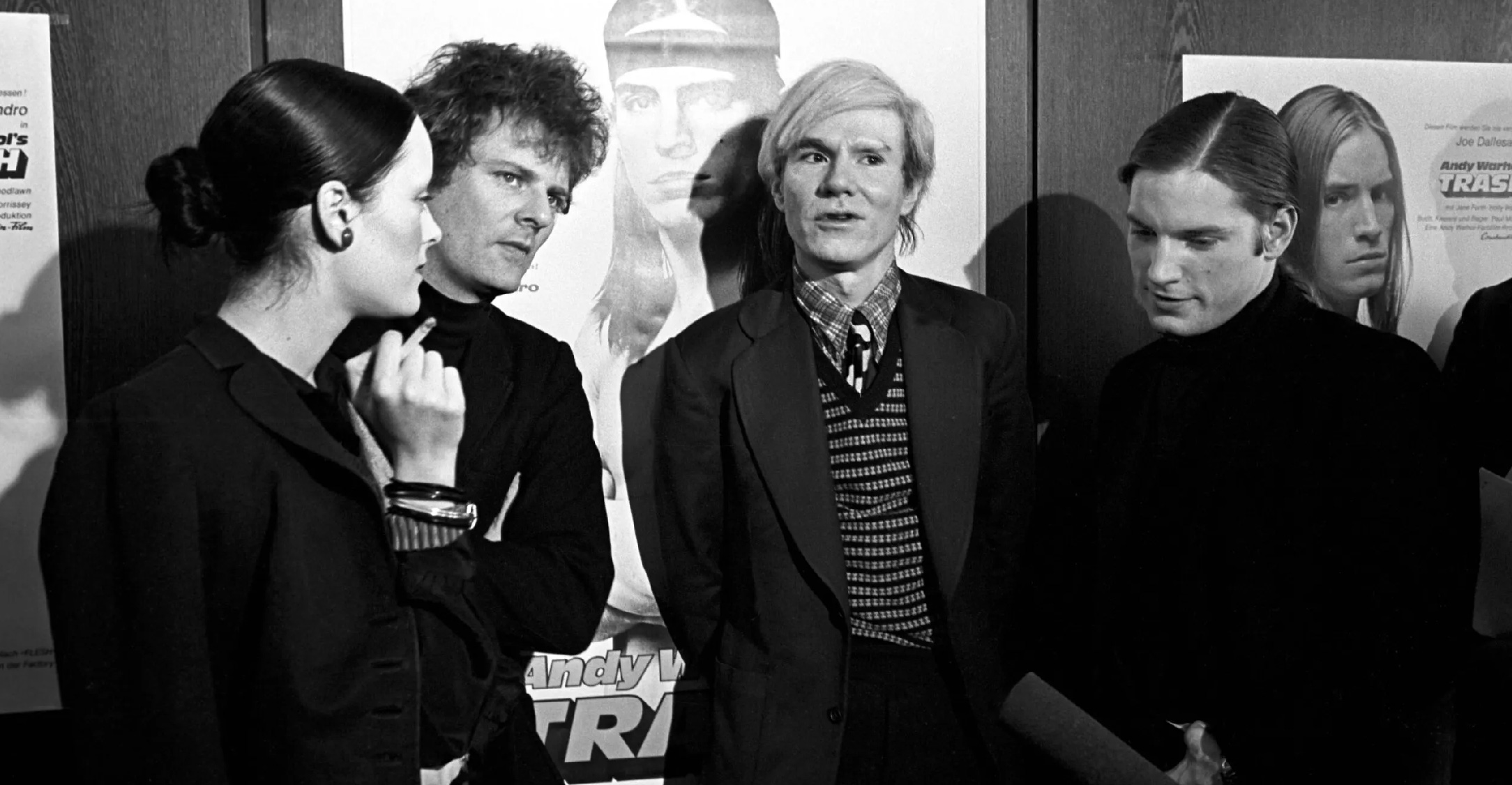

The Factory was not just where Warhol painted. It was where he made films, recorded audio, printed silkscreens, and welcomed anyone interested in getting involved. He worked with Gerard Malanga, Billy Name, Brigid Berlin, and many others known as “superstars.” They were not stars in the Hollywood sense, but rather characters with eccentric personalities and strong personal auras, people who wanted to create something, or simply to be something.

By the mid-1960s, the atmosphere at The Factory began to change. More and more people came, parties happened every night, music played endlessly, and artistic experimentation blended with a hedonistic lifestyle. The Velvet Underground, an experimental rock band that would later become legendary, rehearsed and performed there. Warhol became their manager and infused their performances with visual concepts. Meanwhile, Warhol was also making films such as Sleep (1964), Empire (1965), and Chelsea Girls (1966). These films were long, slow, and often boring. Sometimes they were made with no clear narrative. Essentially, these works were not created to entertain, but to challenge viewers’ expectations of cinema.

The first Factory lasted only until 1967. When the lease expired, Warhol moved the studio to 33 Union Square West. This new location was larger and safer, especially after the attempted assassination by Valerie Solanas in 1968, which nearly took Warhol’s life. Here, The Factory’s atmosphere became more professional. Although creativity remained, the wild and experimental energy began to fade. Warhol turned his focus more toward the business of art, painting portraits of the wealthy and famous, and developing Interview Magazine, one of the era’s most prominent cultural products.

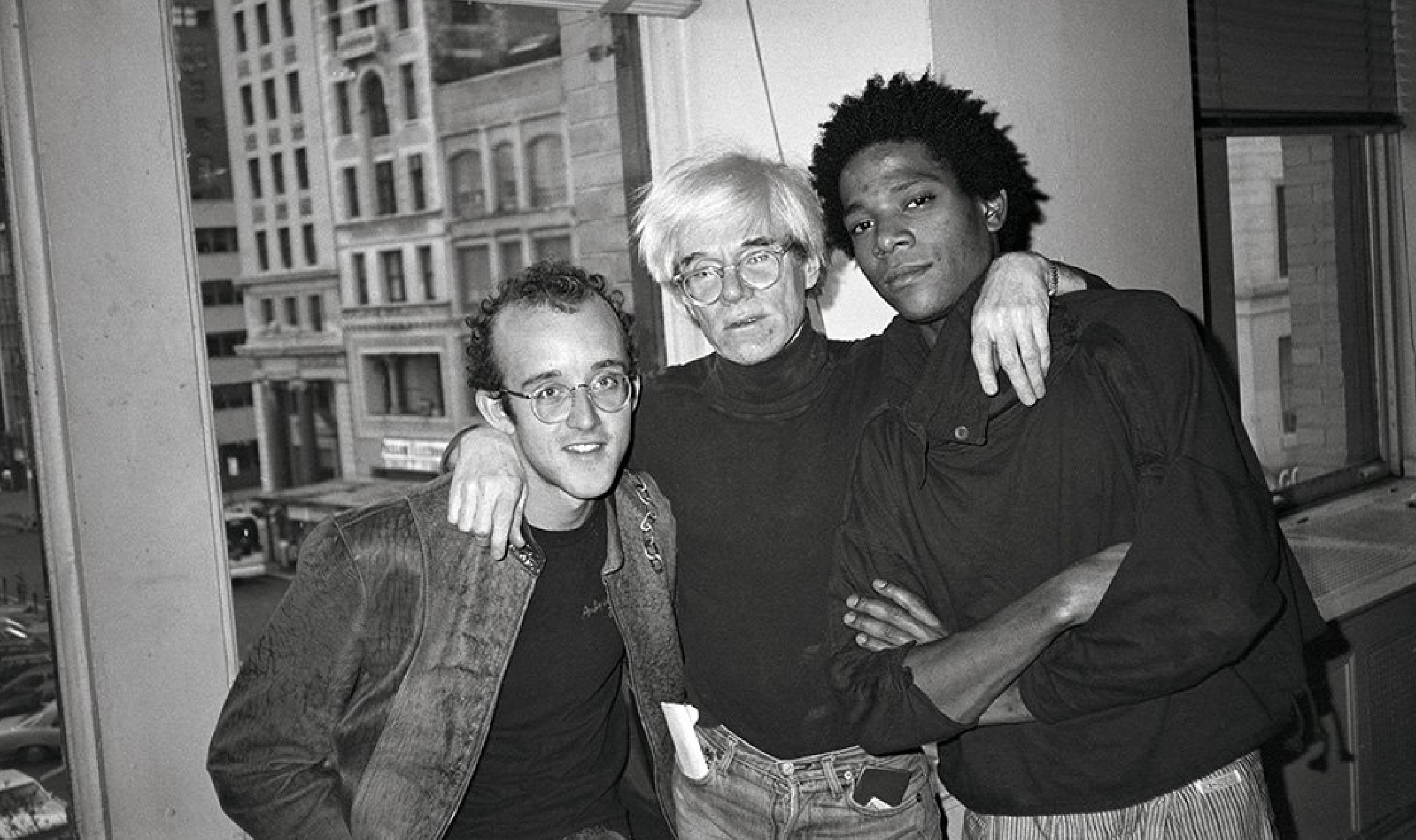

The Factory moved again in 1973 to 860 Broadway, a large building overlooking Union Square. This studio resembled a corporate office more than the subversive space it once was. Warhol continued working there until his death in 1987. During this period, he remained productive, but The Factory’s role as a hub of avant-garde culture had significantly diminished. The unpredictable and eccentric crowd that once defined it was gradually replaced by collectors, editors, and businessmen.

Still, The Factory’s legacy lives on. More than just a physical space, it was a symbol of a shifting perspective on art. It challenged the boundaries between high and low culture, between artist and celebrity, between the creative process and the production process. Warhol’s images of Campbell’s Soup were not meant to mock art, but to assert that these were the visual icons of modern America. His portraits of Marilyn Monroe were not personal tributes, but commentaries on how society constructs and consumes imagery.

Warhol’s major works were born at The Factory. His silkscreen portraits of Elvis, Marilyn, Liz Taylor, Mao Zedong, and Jackie Kennedy enabled rapid reproduction. His experimental films, such as Eat, Blow Job, and My Hustler, were screened in basements, independent theaters, and avant-garde festivals. Interview Magazine, launched in 1969, emerged from The Factory spirit, a mix of gossip, art, fashion, and interviews blended into one inseparable package.

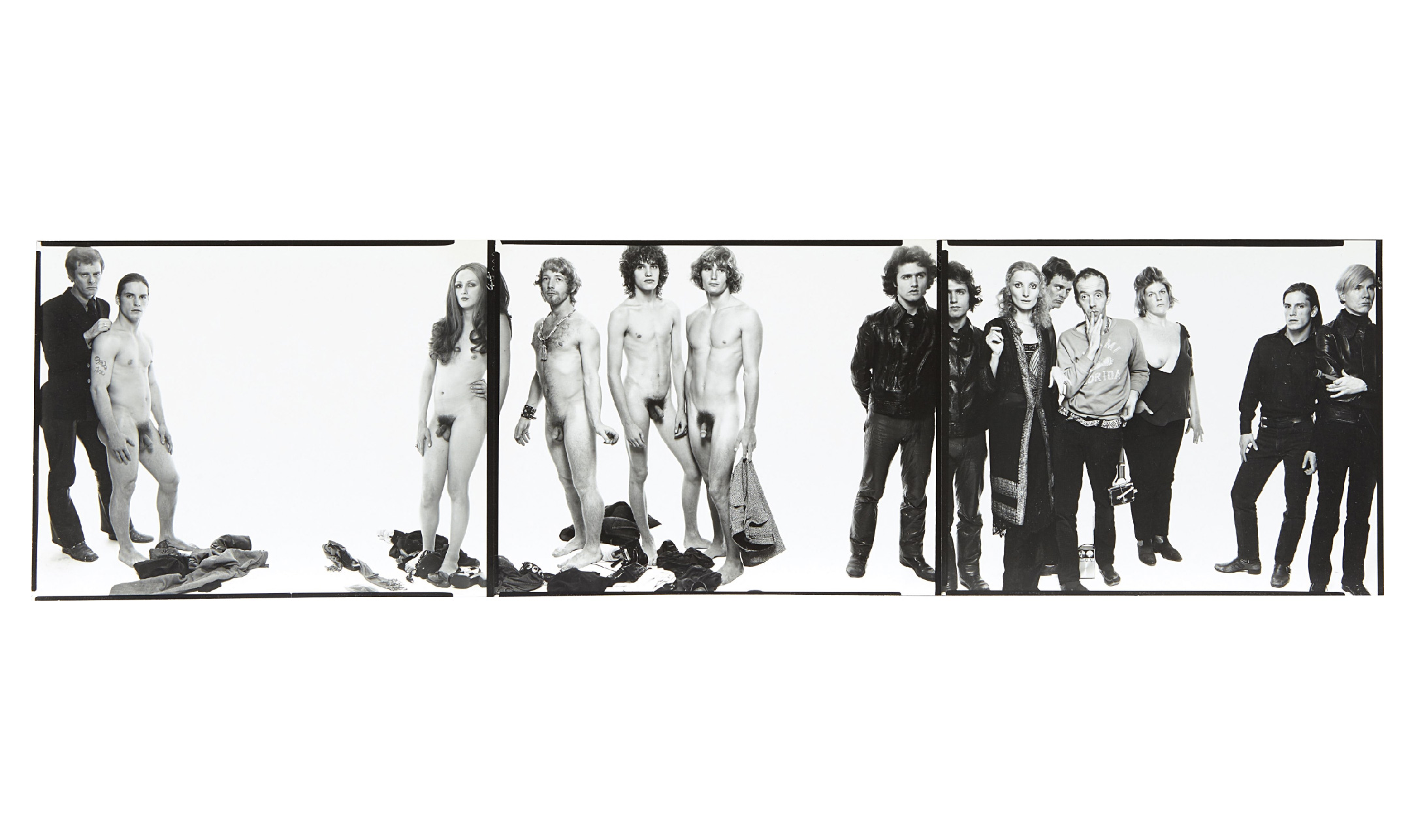

The Factory was also a community space. People came and went not to work in a formal sense, but to talk, debate, pose, do drugs, or simply sit and observe. It became a meeting point for radical thinkers and lost youth, for Vogue models and LGBTQ activists, for street poets and magazine editors. Here, all status could be renegotiated, and all identities could be reassembled.

For many, The Factory was a prototype of what we now call creative networks or urban cultural ecosystems. It was not just a place to make art, but a place to live an artistic lifestyle. Warhol didn’t just make works, he built a world in which those works could live. This is what made The Factory a new idea in art. It didn’t merely respond to its time, it created a new atmosphere that seeped into music, fashion, advertising, politics, and even the ways people talked and dressed.

Warhol understood that in the modern world, image matters more than substance, or at least determines how something is received. So he created The Factory as an image factory, where everyone could be a celebrity for fifteen minutes, and any object could become art if given the right context. It wasn’t Warhol who decided who got to enter, it was time that would determine who remained.

Today, The Factory no longer exists physically, but its influence persists in creative spaces around the world. Alternative galleries, artist collectives, indie recording studios, and even polished social media accounts all, directly or indirectly, inherit The Factory’s spirit: that art no longer belongs to a select elite, but is the product of fluid, spontaneous, and uncertain social interaction.

The Factory was a space where the boundary between art and life dissolved. And from that blur, something entirely new was born, something unrepeatable, but always remembered and open to reinterpretation.