To Feel is to See: Tracing Memory and Home in Do Ho Suh’s Walk the House

On our visit to London, we had the privilege of attending Do Ho Suh’s seminal exhibition, Walk the House, at Tate Modern. The exhibition marks Suh’s first solo show in his long-time home base of London—an imprint on his ever-evolving artistic journey, one that tends to the layered questions of home evoked by the many places he inhabits. Its title stems from a childhood memory of the construction of his family’s home in Seoul, where Suh once overheard carpenters use the term “walk the house” in relation to their work onto the hanok. These traditional Korean homes, versatile in structure and easily disassembled and reassembled in new locations, serve as a poignant metaphor for the processes of creating, revitalising, and rupturing homes—processes Suh has continually endured across his movements through Seoul, New York, and London.

Over the course of 30 years, Suh has consistently explored the notion of ‘home’ in relation to the multiplicities of place—those he has entered, inhabited, and left behind. He noted in an interview that this interest began when he moved away from South Korea in 1991 to pursue his studies in the United States: “Really, what happened is that the concept of home only started to exist for me when I left Korea. When I lived there, I didn’t think about it at all.” That distance, he reflects, gave him the vantage point to engage with the memories he had carried across borders and dwellings. “I’ve had an emotional attachment to certain places that I have lived in and left. My work is a way to somehow deal with these departures.”

Upon entry, the exhibition opens with Rubbing/Loving Project: Seoul Home (2013–2022), an attempt to interlace Suh’s memory with the physical trace of his childhood home in Korea. The piece was created using a rubbing technique: Suh returned to the home, covered its exterior with paper, and traced its surface using graphite. He described the process as requiring “precise pressure”—simple in its form, but intense and at times exhausting when engaged on a large scale. Suh revealed that this exhaustion acts as his signal to stop, allowing the physical demand of the process to dictate his departure from it. The technique was then applied to fragments of other former homes, as seen in Rubbing/Loving: Apartment A, 348 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011, USA (2014). In this work, Suh replaced graphite with coloured pencil, marking a noticeable shift in tone. Where his childhood home appears in a solemn grayscale, his New York apartment is rendered with livelier, more poignant colours—perhaps reflective of memories that are sharper, more emotionally resonant, or simply closer in time.

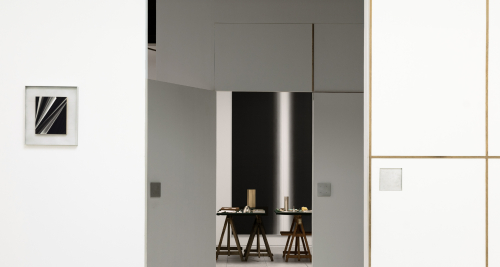

This thread continues into Suh’s more recent installation, Nest/s (2025), which captures the state of liminality in buildings scattered across Seoul, New York, and London. The work pushes against the architectural demand for fixedness and tangibility; instead, it attempts to visualise the invisible qualities of in-between states. What results is what Suh calls an “impossible, continuous” architecture—an ungraspable structure that floats across memory, place, and time. These concerns are approached in a slightly different register in Perfect Home: London, Horsham, New York, Berlin, Providence, Seoul (2024), which reconstructs fragments of home: hallway corners, bathroom sinks, light switches, air conditioning units. Both installations are presented as incomplete, their forms suspended and unresolved. Yet their side-by-side positioning within the exhibition creates a subtle thread, a quiet continuity that resists chronology. Here, Suh suggests that the act of remembering has no origin point or definitive end; memory can be sparked by unexpected encounters, not necessarily with specific objects, but with spaces—encounters that reignite moments thought to be dormant.

As viewers, we become aware that the exhibition is built from Suh’s own memories, but in inhabiting these spaces—even momentarily—we are inevitably reminded of our own. His craftsmanship evokes the layered nature of memory work, in which one person’s experience becomes a portal for another’s reflection. Suh proves himself a master of arrangement, capable of fabricating intimacy within the neutrality of the white cube. He noted his intention of constructing fabric architecture: “I chose fabric for the architectural pieces because the translucency means that you can bring the surrounding space into the piece, blurring the boundary between the artwork and the visitors’ bodies,” Suh explains. “I want visitors to see the architecture of the museum through my work—that it’s not just a white space for art. If you’re inside a fabric architecture piece, you’re actually part of the piece: you activate it.”

In this gesture, Suh opens up a broader invitation—not just to view, but to ponder alongside him. To dwell in the question of what makes a home. To think of the doorways, windows, and walls we’ve moved through, and ask ourselves: How do we call a place home? And what, ultimately, constitutes the making of one?