Kei Imazu: Weaving the Threads of the Past

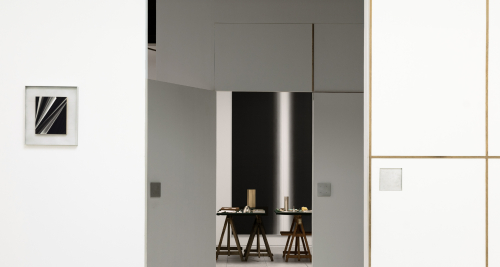

The exhibition hall of Museum MACAN has been transformed into a space to contain the ebbs and flows of histories, mimicking the ripple-like waves of time. The Sea is Barely Wrinkle is Kei Imazu’s first solo exhibition at the museum and she invites visitors to enter a fragmented sea of memories– woven through her poetic and political work that touches on the intersecting themes of colonialism, ecology, and mythology. In the presence of one of her pieces, a Nyi Roro Kidul sculpture, we sat down with the Bandung-based Japanese artist (b. Japan, 1980) to discuss her practice.

Since the beginnings of her artistic career, Kei has always had a distinct approach to forming materials. This particular exhibition showcases her expertise in blending traditional artistic techniques with digital technologies to re-articulate and reconfigure history; moving away from its fixation with linearity and forming an ambivalence into materialities. Thus, her artistic pieces can be interpreted as a twist on restoration through Kei’s coalescence of traces of memory, power, and of place in her practice as she draws upon the old, the new and everything in between. Her relocation to Bandung in 2018 has brought more depth into her research, as she continues to cross the boundaries of temporality and geography to uncover Southeast Asia’s colonial legacy and ecological transformation(s), with a particular focus on Indonesia.

Throughout her work, Kei explores the intertwining of these two themes–colonialism and ecology–with local mythology. She believes that the narratives that grow within a community serve as an entry point to explore the relationships between people, history, and nature. The presence of Nyi Roro Kidul, for instance, greets visitors upon entry into the exhibition and she stands as an ode to the Javanese’s worship of natural and spiritual powers for their protection of Java, against colonial ambition and those who threaten the archipelago. Nyi Roro Kidul, the fabled Queen of the Southern Sea in Javanese lore, is positioned here as a counterbalance to worldly power.

“I see her as a representation of nature, one that can overcome human ambition,” Kei says, as she reflects on her process.

The play upon the symbols of history intensified as we moved towards the center of the exhibition space and witnessed its centrepiece: a remake of the 1628 shipwreck of a VOC trade ship that sailed from Batavia to Amsterdam. The ship, never reaching its destination, sank off the coast of Australia in June 1629. Kei’s interest piqued at the very act of rupture–how a vessel of colonial grandeur ultimately became a monument to failure.

“Maybe it’s a kind of karma,” she thought. “Perhaps nature was angry at human greed.”

As we move through the exhibition, her painting of a sunken Jakarta catches our eye. Here, Kei goes beyond addressing today’s climate crisis or urban mismanagement and points directly to the failure that is rooted into the city’s development. “The VOC never designed this city for its people. They only came to extract resources. We’re just now feeling the consequences of that greed.”

As an artist, Kei finds parallel in historical facts and mythology alike and poetically addresses them. For her, it is at the intersection of the two where we, as humans, might discover a vantage point from which to view history.

The exposure towards Japanese and Indonesian cultures has given Kei the curiosity to investigate the history that intertwined across the two nations. Upon exploring the archive of Japan’s occupation, she was exposed to the flaws of its narration on Indonesian histories; Kei discovered the limited access to Indonesia’s own history – as many crucial documents and archives of Indonesian materials are exclusively stored in the Netherlands. “If you trace back the last two centuries of Indonesian history, the archives are all over there,” she says. “And even then, they’re written from a Dutch perspective.”

This realization prompted a bigger question for Kei: who writes history, and who gets forgotten? Fascinated by maps, she came to understand that historical archives are rarely neutral. “Those (colonial) maps were created to locate plantations; they were tools of exploitation,” Kei asserts. “They weren’t made for the local people, not for us.”

At the same time, Indonesian communities possess a strong oral tradition–stories passed down from mouth to mouth, generation to generation. “I want to show that this too is a valid form of archiving,” says Kei. “Not all archives need to be written documents. Myths, folktales, lived experiences—they’re all legitimate parts of our history.”

Through a multidisciplinary approach, Kei combines traditional techniques and digital technologies to craft lively visuals that are likened to dynamic collages. This process allows her to navigate history non-linearly–leaping from century to century, from myth to manuscript, from folklore to hyper-detailed colonial maps– and tends to respect its materials. These are composed as images that are densely layered onto each other, evoking a warm and intimate feeling; characteristic of Kei’s maternal touch. Looking ahead, Kei seeks to expand her practice into new mediums, including sound, to rewrite history on her own terms. “I want to experiment with sound. Maybe sound can become a new way of feeling history,” she says.

Beyond history, Kei also delves into identity. As a Japanese woman living in Indonesia, she observed stark contrasts across its artistic environments. For instance, Kei noted that Indonesia is generally more welcoming to its women artists. She even credits Indonesian women figures like Kartini for shaping the collective perspective on women's roles in history. “Women in Indonesia are amazing. Thumbs up!” she exclaims with a signature blend of humor and meaning.

Through her creative journey, Kei Imazu bridges the gap between colonial archives and the oral traditions of local storytellers. Her work opens up a space for us to ask: Whose history do we believe?