Gion in Simulation: Revisiting a Practice of Drawing

When we first entered the exhibition space of Gion in Simulation, what we saw wasn’t Gion’s work. It was a plotter machine moving slowly across a sheet of paper. Beside it were digital images in 8-bit style being drawn onto the paper by the machine. The work belonged to Abi Rama. He removed the human hand from the drawing process, allowing the machine to replace gesture. There were no impulsive strokes or spontaneous curves. Everything looked rigid, but that was where the reflection emerged. His work stood as an antithesis to the spontaneity, tactility, and playful expression found in Gion’s drawings, while simultaneously bringing us back to the simplicity of drawing.

Next to Abi Rama’s work stood something resembling a school presentation board, covered with fragments of paintings, crayon scribbles, and various letters that could be attached with magnets. Ipeh Nur hung her drawings like an attendance list, layered with texts, paper cuttings, and irregular additions. Behind each piece lay a stored restlessness. Ipeh described this as an attempt to recalibrate how she draws. She didn’t want to merely present finished works, but to also show the act itself, a small ritual that might seem trivial. Gion’s drawing of the Mahabharata fragment titled Not a Black-and-White War served as her point of reflection. Ipeh responded to her inner turmoil by inviting the public to disassemble, rearrange, and create their own compositions. I saw a child drawing and sticking their picture onto the magnetic board. No one objected.

Looking to our left and right, we finally found Gion’s works—this exhibition’s central figure. On the right was a mural of a group of people bound and trapped together, based on one of Gion’s archival drawings. On the left, a series of drawings from key episodes of the Ramayana and Mahabharata that he created in the 1970s. Through this series, Gion presented a critical reinterpretation of transferring wayang stories into the comic medium. Comics, as a popular medium, inevitably reduce the fundamental values and subtleties of classical wayang tales. To begin his wayang drawing series, Gion took a different approach from other Indonesian comic interpretations. He intervened in both characters and settings, turning them into something akin to science fiction. The figures also remained relevant to contemporary sociopolitical contexts.

Wagiono Sunarto, or Gion as he was affectionately known, was born in 1949 and passed away in 2022. He was a visual artist, academic, graphic designer, and visual thinker who placed drawing at the heart of his aesthetic and intellectual practice. As a pivotal figure in the realms of illustration, cartoons, and comics in Indonesia, Gion co-founded the PERSEGI collective and contributed to the New Indonesian Art Movement. Through Gion and his peers in PERSEGI, one can feel the honesty and simplicity of drawing as an art form. His works also amplified the communicative power, joy, and everyday quality of the medium, standing in contrast to the dominant trends in Indonesian art during the 1970s and 1980s, which were heavily focused on abstract lyrical expressions in painting.

The exhibition, held from May 25 to June 22, 2025, at Rubanah Underground Hub, doesn’t place Gion at the center. Instead, his presence wraps around the ways the participating artists think and create. From old PERSEGI archives to wayang drawings stripped of dialogue, from the idea of drawing as a light yet reflective act to the understanding of illustration and cartoons as interventions in visual culture—all of these reappear, resimulated. Curator Chabib Duta Hapsoro explains that the exhibition not only presents Gion’s archived works, but also showcases the interpretations by the participating artists of Gion’s work and ideas. “The discourse around drawing in Indonesia remains underdeveloped. Yet much of art is rooted in drawing,” he says.

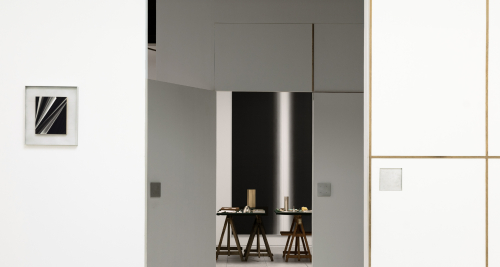

Our steps took me to Dika and Lija’s installation. In front of a white wall stood a table and a cozy chair resembling a small living room. There were fragments of the curatorial text printed in tiny fonts. Some parts had been crossed out. Others were covered with handwritten notes from previous visitors. Some had added small sketches between the paragraphs. In one corner, we were given a marker and invited to join in—rewriting, erasing, or modifying the text. Dika and Lija welcomed us in, turning what is usually treated as sacred writing into something fluid, flexible, and open to tampering. They echoed Gion’s habit of leaving behind notes and doodles—sometimes unfinished, sometimes reappearing after being erased.

At one end of the room, a dark projection screen flickered to life. On it, Iman Anggoro and Gina Adita presented a music video. There was no clear narrative, only sequences of shapes and colors in motion. Sometimes spirals, sometimes fragmented lines, sometimes shifting text. Gion may never have imagined a video like this, but its narrative rhythm felt familiar. There was a beginning, a tension, and a quiet explosion at the end. The visuals didn’t depict anything directly, but offered enough space for viewers to assign their own meanings. In the silence of the room, I imagined Gion sitting in a corner, smiling as he took notes.

Not every visitor seemed to read the long texts or follow the historical references. But many lingered in front of the works. Some even drew, wrote, or added something of their own. Simulation doesn’t mean repetition. It acts as a trigger. As Bambang Budjono said in the exhibition’s discussion, “This exhibition lets us see both the past and the present.”